Volume 13, Issue 1 (3-2025)

Jorjani Biomed J 2025, 13(1): 37-43 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Ghasdi S, Rami M, Habibi A. The effect of six weeks HIIT exercise on the gene expression of some inflammatory and anti-inflammatory markers of hippocampal tissue in aged male Wistar rats. Jorjani Biomed J 2025; 13 (1) :37-43

URL: http://goums.ac.ir/jorjanijournal/article-1-1079-en.html

URL: http://goums.ac.ir/jorjanijournal/article-1-1079-en.html

1- Department of Sport Physiology, Faculty of Sport Sciences, Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz, Ahvaz, Iran

2- Department of Sport Physiology, Faculty of Sport Sciences, Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz, Ahvaz, Iran ,m.rami@scu.ac.ir

2- Department of Sport Physiology, Faculty of Sport Sciences, Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz, Ahvaz, Iran ,

Full-Text [PDF 540 kb]

(492 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2703 Views)

Results

IL-6 expression

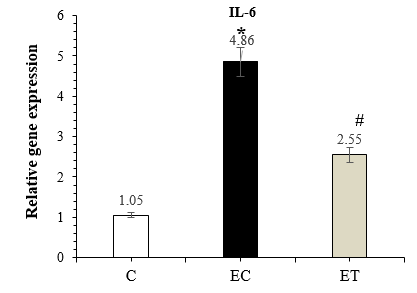

The results of the one-way ANOVA showed a significant difference between groups (P-Value =0.001) for IL-6 gene expression, and the results of Tuckey’s post-hoc test showed a significant increase in the expression of IL-6 in the EC group compared to the C group (P-Value =0.001), while IL-6 expression significantly decreased by HIIT (P-Value =0.001) in the ET group compared to the EC group (Figure 1).

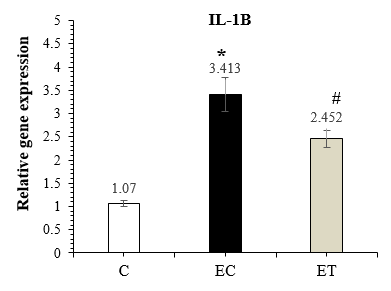

The results of the one-way ANOVA showed a significant difference between groups (P-Value =0.001) for IL-1β expression, and the results of Tuckey post-hoc test showed a significant increase in the expression of IL-1β in the EC group compared to the C (P-Value =0.001), whereas IL-1β expression significantly decreased by HIIT (P-Value =0.001) in the ET group compared to the EC group (Figure 2).

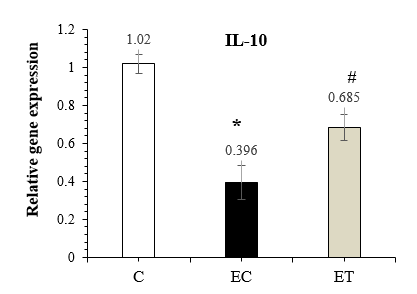

The results of the one-way ANOVA showed a significant difference between groups (P-Value =0.001) for IL-10 expression, and the results of Tuckey post-hoc test showed a significant decrease in IL-10 expression in the EC group compared to the C (P-Value =0.001), while IL-10 expression significantly increased by HIIT (P-Value =0.001) in the ET group compared to the EC group (Figure 3).

The results of the one-way ANOVA showed a significant difference between groups for SOD (P-Value =0.001) and MDA (P-Value =0.001), and the results of Tuckey post-hoc test showed a significant increase in the expression of IL-10 in the EC group compared to the C (P-Value =0.001), and the average of them decreased significantly by HIIT (P-Value =0.001) in the ET group compared to the EC group (Figure 4).

Discussion

This study investigated the effects of HIIT on some inflammatory and anti-inflammatory markers in the hippocampal tissue of aged rats. Examination of the results showed that the mean expression level of IL-6 and IL-1β significantly increased, while the mean expression level of IL-10 significantly decreased in the hippocampus of aged control rats compared to the control group. However, after six weeks of HIIT, the mean expression level of IL-6 and IL-1β significantly decreased, whereas the mean expression level of IL-10 significantly increased in the hippocampus of aged trained rats compared to the control group. The results of some recent studies are also consistent with the results of the present study and have shown that the mean expression levels of IL-6 and IL-1β with the aging process are increased, while IL-10 is decreased (27), which may cause neurodegenerative diseases and dementia (28). However, it is better to perform preparatory training first in elderly and less active groups and then move on to HIIT (29,30). Therefore, it is likely that the inflammatory, anti-inflammatory, and pro-inflammatory effects of HIIT in this study and counteract the increasing effects of aging on oxidative stress may control the age-related decline in hippocampal tissue of trained elderly rats compared to the control elderly group.

IL-6

The results show that IL-6 expression is significantly increased in elderly control samples compared to young control samples. Additionally, samples from older adults who exercised showed a significant decrease compared to controls (1.9 units lower in the exercised sample than in the control group). Therefore, it seems that the hippocampus is sensitive to exercise stress and is affected by exercise intensity. According to the results of studies, there is a relationship between the volume of brain gray matter and the level of this cytokine in elderly people, and it has also been reported that increased levels of IL-6 after inflammation causes memory impairment and neuron loss (31). Signorelli et al. reported that treadmill exercise for more than 5 min did not alter IL-6 levels in elderly subjects. As a result, IL-6 levels were maintained in working muscles after 60 min of exercise in 70-year-old men (32). Another study showed that 12 weeks of combined resistance and aerobic training changed the levels of IL-6, TNF-α, or IL-1β under resting conditions in healthy elderly samples (33). One of the reasons for the inconsistency of the results of the research subjects is that the present study used laboratory animals, providing greater control over the subjects, diet, and living environment, and limited the influence of confounder variables, while other studies used human subjects as exercisers. The study of Shargh and her colleagues showed that a period of endurance exercise reduced IL-6 levels in the plasma of aged rats (34). According to the results of another study, 12 weeks of aerobic training led to a decrease in all pro-inflammatory cytokines, CRP, IL-1, IL-6, and also a significant increase in the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 in elderly patients with coronary artery disease (35). In line with the results of the present study, Abbasi et al. investigated the effect of HIIT swimming on the protein level of IL-6 in the hippocampus of rats. The results showed that eight weeks of HIIT improved brain function and reduced IL-6 in the hippocampus of rats (36). IL-6 release during exercise is independent of TNF-α and increases 100-fold during exercise and with skeletal muscle contraction. In fact, the amount of IL-6 release depends on the intensity and duration of exercise and the volume of muscle groups involved. The cytokine IL-6 released from skeletal muscle inhibits inflammatory markers by stimulating their receptor antagonists and increases the release of anti-inflammatory markers such as IL-10 (37). It seems that in the present study, a decrease in IL-6 expression levels led to decreased levels of inflammatory markers and increased expression levels of IL-10. According to the results of some other studies, it has been stated that the protection of brain cells during exercise is mediated by IL-6 and may be beneficial in neuro-inflammatory diseases, especially those affecting the hippocampus (38).

IL-1β

According to the results of the present study, the expression level of IL-1β in the aged control group significantly increased compared to the control group, and significantly decreased in the aged exercise group compared to the aged control group (In the exercise group, it was 0.9 units lower than the control). In terms of the duration of exercise and its effectiveness, it has been suggested that three weeks of exercise is sufficient to reduce the concentration of amyloid and pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β (39), and performing acute exercise has the opposite effect, as we see in the study by Pedersen et al., (40) and the study of Hamada et al., (41). In the study by Hamada et al., it has been observed that performing acute exercise increases mRNA levels of TNF-α and IL-1β in skeletal muscle in adults aged 66 to 78 years (41). The results of another study show that resistance training induces mRNA expression of IL-1β, IL-2, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and TNF-α in muscle tissue without increasing them in the plasma of recreationally active elderly women (42). In the study conducted by Naderi et al. (43) in the Alzheimer's group who performed resistance exercise, the results showed that there was no significant difference in IL-1β levels compared to the Alzheimer's control group. The results of these studies are inconsistent with the results of the present study, which may be due to the type of exercise protocol and differences in initial IL-1β levels. Another reason could be the time of blood sampling after the last training session, which, in the study of Naderi et al., was performed 48 hours after the last training session, while injuries caused by sports activity can be observed up to 72 hours after the end of training. For this reason, it is possible that the lack of a significant decrease in IL-1β levels is due to the residual effects of the last training session. On the other hand, the results of human studies have suggested the use of exercise training, especially HIIT, in Alzheimer's patients as a strategy for modulating systemic inflammation, which can have a neuroprotective effect (44,45). Therefore, it can be stated that the antioxidant effects of high-intensity intermittent exercise can probably be a modulating factor in regulating inflammation in the central nervous system of elderly individuals. However, on the other hand, studies have also reported that long-term exercise activity at high intensities can itself be a factor in controlling inflammation. In a study by Broderick et al., it was shown that performing moderate-intensity exercise training caused a decrease in expression of IL-1β in the hearts of rats (46). In the study by Sarikhani et al., the effect of HIIT on the levels of IL-1β in the heart of rats was investigated, and the results showed a decrease in its levels after a short-term exercise period (47). Studies have shown that HIIT, causes physiological adaptations, and on the other hand, it may be accompanied by HIIT and an inefficient antioxidant system in the body, causing cellular damage caused by oxidative stress (48,49). It has been shown that HIIT at an intensity close to 80% of maximum speed has been able to significantly regulate and control oxidative stress (50). However, the effects of HIIT on oxidative stress require further investigation. In the present study, due to the lack of assessment of all oxidative stress factors, it is not clear whether this HIIT has controlled and regulated oxidative stress in hippocampal tissue. Therefore, there is a need for more and more detailed studies on the effects of HIIT on oxidative stress in the central nervous system, especially in the hippocampal region.

IL-10

According to the results of this study, the expression level of IL-10 in aged control rats was significantly decreased compared to the control group, and significantly increased in aged exercise rats compared to the aged control group (In the exercise group, it was 0.4 units higher than in the control group). Many studies have been conducted on the effect of exercise on IL-10, and it has changed differently in response to the exercise with different protocols. The results of the present study were inconsistent with the results of the study by Barzegar et al., who performed a period of exercise training with no effect on IL-10 levels. It has been suggested that the response of this anti-inflammatory cytokine to exercise is lower (51). While the study by Dornelers et al. showed that overweight and obese individuals had lower IL-10 levels than the control group, and an increase in its levels was seen immediately after performing exercise (52). They investigated the effect of HIIT on IL-10 levels in overweight men. Their findings indicated that exercise training led to an increase in serum IL-10 levels. This rise in IL-10 is a response to elevated inflammatory cytokines, aimed at suppressing them. However, it appears that short-term training periods do not produce significant changes in the baseline levels of this cytokine (52). In cross-sectional and longitudinal studies, the anti-inflammatory effect of exercise activities and its effect on pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines have been confirmed. IL-10 is positively associated with physical fitness (53) and its effect apparently depends on the intensity of training, and HIIT can change its levels, as we see in the present study, its levels increased following HIIT. One of the possible mechanisms for IL-10 averages following regular exercise training is the balance between Th1 and Th2 cytokines (54). Apparently, exercise training can cause an upregulation of Th2 cytokine production and a relative downregulation of Th1 cytokines, which ultimately leads to an increase in inflammatory cytokines, including IL-10 (40). In addition, adiponectin suppresses Th2 secretion by stimulating prostaglandin synthesis and ultimately affects B-lymphocyte activity to improve inflammation. Therefore, it is possible that exercise training affects IL-10 levels by increasing adiponectin levels. It has also been suggested that exercise can alter IL-10 directly through cytokine production in muscle, adipose tissue, and mononuclear cells, and indirectly through increased insulin sensitivity, increased endothelial function, and weight loss. It has been suggested that exercise training, by downregulating NF-κB, induces IL-10 secretion by T cells and monocytes via the Th2 pathway (54). However, the present study has some limitations, and one of the most important limitations is the type of research subjects, which were laboratory animals, and this limitation may affect its external validity and its generalization to normal societies and humans. Another limitation was the small sample size, and it is possible that using a larger sample size would have had different effects on the results of this study. Also, the duration of six weeks of exercise training is another limitation of this study, and using a longer period of time may have yielded different results.

SOD and MDA

Regarding the two measured side factors MDA and SOD, the results showed that training had a positive effect, reducing the levels of both markers. It seems that elderly rats subjected to HIIT exercises improve their health by strengthening the antioxidant defense system, especially by improving SOD and MDA, through the scavenging of free radicals by antioxidants. These findings are of great help in reducing diseases related to free radicals during the sensitive period of aging. In fact, in the discussion of technical differences in physical activity, it can be stated that the effect of exercise training on the activity of antioxidant enzymes during exercise depends on the amount of oxygen consumption with respect to the intensity, duration and type of exercise. As shown, moderate-intensity endurance exercise caused a decrease in SOD and no change in catalase and glutathione peroxidase (55).

Conclusion

Our findings indicate a significant increase in some inflammatory, anti-inflammatory, and oxidative stress markers during aging. However, the exact mechanism is still unclear. Therefore, based on the available evidence and considering the benefits of HIIT in aging on pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory markers, it can be stated that HIIT-type physical activity may have beneficial effects on preventing neurodegeneration due to its anti-inflammatory properties and could be a promising non-pharmacological strategy for controlling the complications of aging.

Acknowledgement

This article is based on a master's thesis that was conducted with research grant number SCU.SS1404.266. We would like to express our gratitude and appreciation for the cooperation and support from Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz and the Department of Sports Physiology within the Faculty of Sports Sciences at Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz.

Funding sources

None declared.

Ethical statement

The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz with the number SCU. EC. SS. 403.1107.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

S. Gh. and M. R. designed the study. S. Gh. served as principal investigator. S. Gh. collected the data. M. R. analyzed data. M. R. and A. H. were involved in data interpretation and presentation. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Data availability statement

All the data used in this study can be found within the article itself and do not need separate access.

Full-Text: (172 Views)

Introduction

With aging, various changes occur in the body's systems and cells, including brain atrophy, increased oxidative stress, as well as decreased antioxidant defense mechanisms, which contribute to impaired memory, learning, and physical activity (1). In fact, these aging-related changes are major risk factors for the most common neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson's, Alzheimer's, and Huntington's diseases (2). Many age-related changes are associated with risk factors such as changes in cytokine expression levels (3). Cytokines are cell signaling proteins that are secreted to regulate the immune response to various inflammatory processes and injury (4). These cells signaling proteins include pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), and IL-6, and anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 (4). Higher levels of IL-6 were observed in the hippocampal formation and cerebellum of aged rats compared with young adult rats (5). In addition, decreased levels of IL-10 have also been identified in the aged brain (5). Results of studies suggest that age-related decreases in IL-10 levels may contribute to increased brain IL-6 expression in aged rats (6). This imbalance in the anti- and pro-inflammatory balance may be one of the mechanisms contributing to age-related neurodegeneration and brain vulnerability to disease (6).

Increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines have been reported in neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and other chronic conditions (7). Consequently, non-pharmacological and pharmacological interventions targeting cytokines and their signaling pathways have been proposed for therapeutic purposes (8). There is a growing body of evidence that suggests the potential of physical activity to reduce or improve outcomes of common age-related disorders (9). In fact, physical activity may be an important intervention to improve cognitive function in the elderly (10) and may be effective in reducing the progression or onset of neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s (11) and Parkinson’s (12). These beneficial effects of physical activity during aging should be associated with changes in brain cytokine expression. Among the exercises that received attention today is high-intensity interval training (HIIT), which describes exercises that include short, intermittent periods of intense physical activity interspersed with low-intensity exercise or rest periods (13). Statistics show that only about 30% of people have enough time to engage in long-term aerobic exercise activities and they mainly complain about the lack of vitality and fatigue of this type of exercise, but short-term intense interval training, in addition to saving time, has also been reported to have more metabolic and physiological benefits (14).

HIIT has recently become a popular alternative activity due to its time efficiency. Several studies have shown that HIIT improves metabolic dysfunction, lipid profiles, systemic inflammatory markers, cardiac structure and function, and insulin receptors (15-19). Freitas et al. showed that after six weeks of HIIT, antioxidant defenses in cerebellar tissue increased (20); this protocol also reduced inflammatory markers and lipoperoxidation, reducing oxidative stress in the hippocampus. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels and antioxidant defenses were also increased with HIIT (21). It seems that the greater the duration and intensity of exercise, the stronger and more prolonged the immune response. Therefore, it is predicted that repeated bouts of a prolonged and continuous exercise stimulus will reduce the inflammatory response, reflecting an adaptive immune response to physical activity (22). Recent studies have also shown that exercise can alter inflammatory responses in the brain of rats (23) and given that most studies have examined the effects of HIIT have been less studied in the elderly. In fact, less is known about the inflammatory response to HIIT exercise. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the effect of six weeks of HIIT on selected inflammatory and anti-inflammatory genes (IL-10, IL-6, and IL-1β) in the hippocampal tissues of elderly rats.

Methods

Experimental animals

This research was an experimental and applied study conducted in a laboratory with a post-test design with a control group. Accordingly, 21 male Wistar rats were obtained from the animal house of Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz. Based on the size of the previous studies (24,25), this number was selected for each group, and since the aging process has been done for 22 months, the maintenance of this sample size has was more manageable. After that, rats were transferred to the laboratory environment and were kept in eight groups of two and three in transparent polycarbonate cages with a 12:12 light-dark cycle, at a temperature of 20-23 °C, and with free access to food and water. Initially, rats that were intended for old age were selected at 22 months of age and randomly divided into two groups: training and control. At the same time, a young group (10 weeks) was also added to the groups. Therefore, rats were divided into three groups: 1-control group (C), 2-elderly control group (EC), and 3-elderly training group (ET). The intervention lasted six weeks, during which rats underwent HIIT intervention.

HIIT protocol

At the beginning of the exercise protocol, all rats were acclimated to the rodent treadmill conditions for two weeks at a speed of 15 m/min for 15 min per day. Then, 48 h after the last familiarization session, all rats underwent a maximal speed test. The test started at a speed of 10 m/min, and then the treadmill speed was automatically increased by 3 m/min every 3 min until exhaustion. The HIIT protocol in the first week consisted of running on the treadmill for five 2-min intervals at an intensity of 80% of maximum speed. Each interval was followed by 2 min of active rest at 60% of maximum speed. The training schedule in consecutive weeks is shown in Table 1 (26). At the beginning and end of each session, warming up and cooling down were performed for 1 min. After the end of the training period, the hippocampal tissues of the rats were extracted and stored in the freezer.

Hippocampal tissue extraction, Real-time PCR, and SOD and MDA measurement

Forty-eight hours after the last training session, rats were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of 20-30 mg/kg ketamine and 2-3 mg/kg xylazine. Then, hippocampal tissue was isolated and snap-frozen. After RNA extraction using a special kit (Pars Toss, Iran), gene expression was measured using RT-PCR. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a reference gene. LightCycler SW1.1 software was used for comparative gene expression. Primer sequences are shown in Table 2. The Rendox-UK colorimetric method was used to measure the levels of malondialdehyde (MDA) and superoxide dismutase (SOD).

Statistical analysis

In this study, the Shapiro-Wilk test was used to check the normality of the data and the Levene test was used to check the homogeneity of variances. Also, the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test and then the Tukey’s post-hoc test were used to check the means of the variables and compare the groups pairwise. SPSS version 19 software was used to analyze the data. Statistical significance level was 0.05.

With aging, various changes occur in the body's systems and cells, including brain atrophy, increased oxidative stress, as well as decreased antioxidant defense mechanisms, which contribute to impaired memory, learning, and physical activity (1). In fact, these aging-related changes are major risk factors for the most common neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson's, Alzheimer's, and Huntington's diseases (2). Many age-related changes are associated with risk factors such as changes in cytokine expression levels (3). Cytokines are cell signaling proteins that are secreted to regulate the immune response to various inflammatory processes and injury (4). These cells signaling proteins include pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), and IL-6, and anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 (4). Higher levels of IL-6 were observed in the hippocampal formation and cerebellum of aged rats compared with young adult rats (5). In addition, decreased levels of IL-10 have also been identified in the aged brain (5). Results of studies suggest that age-related decreases in IL-10 levels may contribute to increased brain IL-6 expression in aged rats (6). This imbalance in the anti- and pro-inflammatory balance may be one of the mechanisms contributing to age-related neurodegeneration and brain vulnerability to disease (6).

Increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines have been reported in neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and other chronic conditions (7). Consequently, non-pharmacological and pharmacological interventions targeting cytokines and their signaling pathways have been proposed for therapeutic purposes (8). There is a growing body of evidence that suggests the potential of physical activity to reduce or improve outcomes of common age-related disorders (9). In fact, physical activity may be an important intervention to improve cognitive function in the elderly (10) and may be effective in reducing the progression or onset of neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s (11) and Parkinson’s (12). These beneficial effects of physical activity during aging should be associated with changes in brain cytokine expression. Among the exercises that received attention today is high-intensity interval training (HIIT), which describes exercises that include short, intermittent periods of intense physical activity interspersed with low-intensity exercise or rest periods (13). Statistics show that only about 30% of people have enough time to engage in long-term aerobic exercise activities and they mainly complain about the lack of vitality and fatigue of this type of exercise, but short-term intense interval training, in addition to saving time, has also been reported to have more metabolic and physiological benefits (14).

HIIT has recently become a popular alternative activity due to its time efficiency. Several studies have shown that HIIT improves metabolic dysfunction, lipid profiles, systemic inflammatory markers, cardiac structure and function, and insulin receptors (15-19). Freitas et al. showed that after six weeks of HIIT, antioxidant defenses in cerebellar tissue increased (20); this protocol also reduced inflammatory markers and lipoperoxidation, reducing oxidative stress in the hippocampus. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels and antioxidant defenses were also increased with HIIT (21). It seems that the greater the duration and intensity of exercise, the stronger and more prolonged the immune response. Therefore, it is predicted that repeated bouts of a prolonged and continuous exercise stimulus will reduce the inflammatory response, reflecting an adaptive immune response to physical activity (22). Recent studies have also shown that exercise can alter inflammatory responses in the brain of rats (23) and given that most studies have examined the effects of HIIT have been less studied in the elderly. In fact, less is known about the inflammatory response to HIIT exercise. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the effect of six weeks of HIIT on selected inflammatory and anti-inflammatory genes (IL-10, IL-6, and IL-1β) in the hippocampal tissues of elderly rats.

Methods

Experimental animals

This research was an experimental and applied study conducted in a laboratory with a post-test design with a control group. Accordingly, 21 male Wistar rats were obtained from the animal house of Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz. Based on the size of the previous studies (24,25), this number was selected for each group, and since the aging process has been done for 22 months, the maintenance of this sample size has was more manageable. After that, rats were transferred to the laboratory environment and were kept in eight groups of two and three in transparent polycarbonate cages with a 12:12 light-dark cycle, at a temperature of 20-23 °C, and with free access to food and water. Initially, rats that were intended for old age were selected at 22 months of age and randomly divided into two groups: training and control. At the same time, a young group (10 weeks) was also added to the groups. Therefore, rats were divided into three groups: 1-control group (C), 2-elderly control group (EC), and 3-elderly training group (ET). The intervention lasted six weeks, during which rats underwent HIIT intervention.

HIIT protocol

At the beginning of the exercise protocol, all rats were acclimated to the rodent treadmill conditions for two weeks at a speed of 15 m/min for 15 min per day. Then, 48 h after the last familiarization session, all rats underwent a maximal speed test. The test started at a speed of 10 m/min, and then the treadmill speed was automatically increased by 3 m/min every 3 min until exhaustion. The HIIT protocol in the first week consisted of running on the treadmill for five 2-min intervals at an intensity of 80% of maximum speed. Each interval was followed by 2 min of active rest at 60% of maximum speed. The training schedule in consecutive weeks is shown in Table 1 (26). At the beginning and end of each session, warming up and cooling down were performed for 1 min. After the end of the training period, the hippocampal tissues of the rats were extracted and stored in the freezer.

Hippocampal tissue extraction, Real-time PCR, and SOD and MDA measurement

Forty-eight hours after the last training session, rats were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of 20-30 mg/kg ketamine and 2-3 mg/kg xylazine. Then, hippocampal tissue was isolated and snap-frozen. After RNA extraction using a special kit (Pars Toss, Iran), gene expression was measured using RT-PCR. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a reference gene. LightCycler SW1.1 software was used for comparative gene expression. Primer sequences are shown in Table 2. The Rendox-UK colorimetric method was used to measure the levels of malondialdehyde (MDA) and superoxide dismutase (SOD).

Statistical analysis

In this study, the Shapiro-Wilk test was used to check the normality of the data and the Levene test was used to check the homogeneity of variances. Also, the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test and then the Tukey’s post-hoc test were used to check the means of the variables and compare the groups pairwise. SPSS version 19 software was used to analyze the data. Statistical significance level was 0.05.

Results

IL-6 expression

The results of the one-way ANOVA showed a significant difference between groups (P-Value =0.001) for IL-6 gene expression, and the results of Tuckey’s post-hoc test showed a significant increase in the expression of IL-6 in the EC group compared to the C group (P-Value =0.001), while IL-6 expression significantly decreased by HIIT (P-Value =0.001) in the ET group compared to the EC group (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Comparison of IL-6 expression in the C, EC, and ET groups 48 hours after the last training session (Mean ± SD). * Indicates a significant increase in the EC group compared to the C group. # Indicates a significant decrease in the ET group compared to the EC group. Abbreviations: C: Control group, EC: Elderly Control group, and ET: Elderly Training group. |

The results of the one-way ANOVA showed a significant difference between groups (P-Value =0.001) for IL-1β expression, and the results of Tuckey post-hoc test showed a significant increase in the expression of IL-1β in the EC group compared to the C (P-Value =0.001), whereas IL-1β expression significantly decreased by HIIT (P-Value =0.001) in the ET group compared to the EC group (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Comparison of IL-1β expression in the C, EC, and ET groups 48 hours after the last training session (Mean ± SD). * Indicates a significant increase in the EC group compared to the C group. # Indicates a significant decrease in the ET group compared to the EC group. Abbreviations: C: Control group, EC: Elderly Control group, and ET: Elderly Training group. |

The results of the one-way ANOVA showed a significant difference between groups (P-Value =0.001) for IL-10 expression, and the results of Tuckey post-hoc test showed a significant decrease in IL-10 expression in the EC group compared to the C (P-Value =0.001), while IL-10 expression significantly increased by HIIT (P-Value =0.001) in the ET group compared to the EC group (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Comparison of IL-10 expression in the C, EC, and ET groups 48 hours after the last training session (Mean ± SD). * Indicates a significant decrease in the EC group compared to the C group. # Indicates a significant increase in the ET group compared to the EC group. Abbreviations: C: Control group, EC: Elderly Control group, and ET: Elderly Training group. |

The results of the one-way ANOVA showed a significant difference between groups for SOD (P-Value =0.001) and MDA (P-Value =0.001), and the results of Tuckey post-hoc test showed a significant increase in the expression of IL-10 in the EC group compared to the C (P-Value =0.001), and the average of them decreased significantly by HIIT (P-Value =0.001) in the ET group compared to the EC group (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Comparison of SOD (a) and MDA (b) in the C, EC, and ET groups 48 hours after the last training session (Mean ± SD). * Indicates a significant difference in the EC group compared to the C group. # Indicates a significant difference in the ET group compared to the EC group. Abbreviations: C: Control group, EC: Elderly Control group, and ET: Elderly Training group. |

Discussion

This study investigated the effects of HIIT on some inflammatory and anti-inflammatory markers in the hippocampal tissue of aged rats. Examination of the results showed that the mean expression level of IL-6 and IL-1β significantly increased, while the mean expression level of IL-10 significantly decreased in the hippocampus of aged control rats compared to the control group. However, after six weeks of HIIT, the mean expression level of IL-6 and IL-1β significantly decreased, whereas the mean expression level of IL-10 significantly increased in the hippocampus of aged trained rats compared to the control group. The results of some recent studies are also consistent with the results of the present study and have shown that the mean expression levels of IL-6 and IL-1β with the aging process are increased, while IL-10 is decreased (27), which may cause neurodegenerative diseases and dementia (28). However, it is better to perform preparatory training first in elderly and less active groups and then move on to HIIT (29,30). Therefore, it is likely that the inflammatory, anti-inflammatory, and pro-inflammatory effects of HIIT in this study and counteract the increasing effects of aging on oxidative stress may control the age-related decline in hippocampal tissue of trained elderly rats compared to the control elderly group.

IL-6

The results show that IL-6 expression is significantly increased in elderly control samples compared to young control samples. Additionally, samples from older adults who exercised showed a significant decrease compared to controls (1.9 units lower in the exercised sample than in the control group). Therefore, it seems that the hippocampus is sensitive to exercise stress and is affected by exercise intensity. According to the results of studies, there is a relationship between the volume of brain gray matter and the level of this cytokine in elderly people, and it has also been reported that increased levels of IL-6 after inflammation causes memory impairment and neuron loss (31). Signorelli et al. reported that treadmill exercise for more than 5 min did not alter IL-6 levels in elderly subjects. As a result, IL-6 levels were maintained in working muscles after 60 min of exercise in 70-year-old men (32). Another study showed that 12 weeks of combined resistance and aerobic training changed the levels of IL-6, TNF-α, or IL-1β under resting conditions in healthy elderly samples (33). One of the reasons for the inconsistency of the results of the research subjects is that the present study used laboratory animals, providing greater control over the subjects, diet, and living environment, and limited the influence of confounder variables, while other studies used human subjects as exercisers. The study of Shargh and her colleagues showed that a period of endurance exercise reduced IL-6 levels in the plasma of aged rats (34). According to the results of another study, 12 weeks of aerobic training led to a decrease in all pro-inflammatory cytokines, CRP, IL-1, IL-6, and also a significant increase in the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 in elderly patients with coronary artery disease (35). In line with the results of the present study, Abbasi et al. investigated the effect of HIIT swimming on the protein level of IL-6 in the hippocampus of rats. The results showed that eight weeks of HIIT improved brain function and reduced IL-6 in the hippocampus of rats (36). IL-6 release during exercise is independent of TNF-α and increases 100-fold during exercise and with skeletal muscle contraction. In fact, the amount of IL-6 release depends on the intensity and duration of exercise and the volume of muscle groups involved. The cytokine IL-6 released from skeletal muscle inhibits inflammatory markers by stimulating their receptor antagonists and increases the release of anti-inflammatory markers such as IL-10 (37). It seems that in the present study, a decrease in IL-6 expression levels led to decreased levels of inflammatory markers and increased expression levels of IL-10. According to the results of some other studies, it has been stated that the protection of brain cells during exercise is mediated by IL-6 and may be beneficial in neuro-inflammatory diseases, especially those affecting the hippocampus (38).

IL-1β

According to the results of the present study, the expression level of IL-1β in the aged control group significantly increased compared to the control group, and significantly decreased in the aged exercise group compared to the aged control group (In the exercise group, it was 0.9 units lower than the control). In terms of the duration of exercise and its effectiveness, it has been suggested that three weeks of exercise is sufficient to reduce the concentration of amyloid and pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β (39), and performing acute exercise has the opposite effect, as we see in the study by Pedersen et al., (40) and the study of Hamada et al., (41). In the study by Hamada et al., it has been observed that performing acute exercise increases mRNA levels of TNF-α and IL-1β in skeletal muscle in adults aged 66 to 78 years (41). The results of another study show that resistance training induces mRNA expression of IL-1β, IL-2, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and TNF-α in muscle tissue without increasing them in the plasma of recreationally active elderly women (42). In the study conducted by Naderi et al. (43) in the Alzheimer's group who performed resistance exercise, the results showed that there was no significant difference in IL-1β levels compared to the Alzheimer's control group. The results of these studies are inconsistent with the results of the present study, which may be due to the type of exercise protocol and differences in initial IL-1β levels. Another reason could be the time of blood sampling after the last training session, which, in the study of Naderi et al., was performed 48 hours after the last training session, while injuries caused by sports activity can be observed up to 72 hours after the end of training. For this reason, it is possible that the lack of a significant decrease in IL-1β levels is due to the residual effects of the last training session. On the other hand, the results of human studies have suggested the use of exercise training, especially HIIT, in Alzheimer's patients as a strategy for modulating systemic inflammation, which can have a neuroprotective effect (44,45). Therefore, it can be stated that the antioxidant effects of high-intensity intermittent exercise can probably be a modulating factor in regulating inflammation in the central nervous system of elderly individuals. However, on the other hand, studies have also reported that long-term exercise activity at high intensities can itself be a factor in controlling inflammation. In a study by Broderick et al., it was shown that performing moderate-intensity exercise training caused a decrease in expression of IL-1β in the hearts of rats (46). In the study by Sarikhani et al., the effect of HIIT on the levels of IL-1β in the heart of rats was investigated, and the results showed a decrease in its levels after a short-term exercise period (47). Studies have shown that HIIT, causes physiological adaptations, and on the other hand, it may be accompanied by HIIT and an inefficient antioxidant system in the body, causing cellular damage caused by oxidative stress (48,49). It has been shown that HIIT at an intensity close to 80% of maximum speed has been able to significantly regulate and control oxidative stress (50). However, the effects of HIIT on oxidative stress require further investigation. In the present study, due to the lack of assessment of all oxidative stress factors, it is not clear whether this HIIT has controlled and regulated oxidative stress in hippocampal tissue. Therefore, there is a need for more and more detailed studies on the effects of HIIT on oxidative stress in the central nervous system, especially in the hippocampal region.

IL-10

According to the results of this study, the expression level of IL-10 in aged control rats was significantly decreased compared to the control group, and significantly increased in aged exercise rats compared to the aged control group (In the exercise group, it was 0.4 units higher than in the control group). Many studies have been conducted on the effect of exercise on IL-10, and it has changed differently in response to the exercise with different protocols. The results of the present study were inconsistent with the results of the study by Barzegar et al., who performed a period of exercise training with no effect on IL-10 levels. It has been suggested that the response of this anti-inflammatory cytokine to exercise is lower (51). While the study by Dornelers et al. showed that overweight and obese individuals had lower IL-10 levels than the control group, and an increase in its levels was seen immediately after performing exercise (52). They investigated the effect of HIIT on IL-10 levels in overweight men. Their findings indicated that exercise training led to an increase in serum IL-10 levels. This rise in IL-10 is a response to elevated inflammatory cytokines, aimed at suppressing them. However, it appears that short-term training periods do not produce significant changes in the baseline levels of this cytokine (52). In cross-sectional and longitudinal studies, the anti-inflammatory effect of exercise activities and its effect on pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines have been confirmed. IL-10 is positively associated with physical fitness (53) and its effect apparently depends on the intensity of training, and HIIT can change its levels, as we see in the present study, its levels increased following HIIT. One of the possible mechanisms for IL-10 averages following regular exercise training is the balance between Th1 and Th2 cytokines (54). Apparently, exercise training can cause an upregulation of Th2 cytokine production and a relative downregulation of Th1 cytokines, which ultimately leads to an increase in inflammatory cytokines, including IL-10 (40). In addition, adiponectin suppresses Th2 secretion by stimulating prostaglandin synthesis and ultimately affects B-lymphocyte activity to improve inflammation. Therefore, it is possible that exercise training affects IL-10 levels by increasing adiponectin levels. It has also been suggested that exercise can alter IL-10 directly through cytokine production in muscle, adipose tissue, and mononuclear cells, and indirectly through increased insulin sensitivity, increased endothelial function, and weight loss. It has been suggested that exercise training, by downregulating NF-κB, induces IL-10 secretion by T cells and monocytes via the Th2 pathway (54). However, the present study has some limitations, and one of the most important limitations is the type of research subjects, which were laboratory animals, and this limitation may affect its external validity and its generalization to normal societies and humans. Another limitation was the small sample size, and it is possible that using a larger sample size would have had different effects on the results of this study. Also, the duration of six weeks of exercise training is another limitation of this study, and using a longer period of time may have yielded different results.

SOD and MDA

Regarding the two measured side factors MDA and SOD, the results showed that training had a positive effect, reducing the levels of both markers. It seems that elderly rats subjected to HIIT exercises improve their health by strengthening the antioxidant defense system, especially by improving SOD and MDA, through the scavenging of free radicals by antioxidants. These findings are of great help in reducing diseases related to free radicals during the sensitive period of aging. In fact, in the discussion of technical differences in physical activity, it can be stated that the effect of exercise training on the activity of antioxidant enzymes during exercise depends on the amount of oxygen consumption with respect to the intensity, duration and type of exercise. As shown, moderate-intensity endurance exercise caused a decrease in SOD and no change in catalase and glutathione peroxidase (55).

Conclusion

Our findings indicate a significant increase in some inflammatory, anti-inflammatory, and oxidative stress markers during aging. However, the exact mechanism is still unclear. Therefore, based on the available evidence and considering the benefits of HIIT in aging on pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory markers, it can be stated that HIIT-type physical activity may have beneficial effects on preventing neurodegeneration due to its anti-inflammatory properties and could be a promising non-pharmacological strategy for controlling the complications of aging.

Acknowledgement

This article is based on a master's thesis that was conducted with research grant number SCU.SS1404.266. We would like to express our gratitude and appreciation for the cooperation and support from Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz and the Department of Sports Physiology within the Faculty of Sports Sciences at Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz.

Funding sources

None declared.

Ethical statement

The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz with the number SCU. EC. SS. 403.1107.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

S. Gh. and M. R. designed the study. S. Gh. served as principal investigator. S. Gh. collected the data. M. R. analyzed data. M. R. and A. H. were involved in data interpretation and presentation. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Data availability statement

All the data used in this study can be found within the article itself and do not need separate access.

Type of Article: Original article |

Subject:

Health

Received: 2024/05/19 | Accepted: 2025/03/16 | Published: 2025/12/8

Received: 2024/05/19 | Accepted: 2025/03/16 | Published: 2025/12/8

References

1. Apostolova LG, Green AE, Babakchanian S, Hwang KS, Chou Y-Y, Toga AW, et al. Hippocampal atrophy and ventricular enlargement in normal aging, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and Alzheimer Disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2012;26(1):17-27. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

2. Farooqui T, Farooqui AA. Aging: an important factor for the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases. Mech Ageing Dev. 2009;130(4):203-15. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

3. Sparkman NL, Johnson RW. Neuroinflammation associated with aging sensitizes the brain to the effects of infection or stress. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2008;15(4-6):323-30. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

4. Godbout JP, Johnson RW. Age and neuroinflammation: a lifetime of psychoneuroimmune consequences. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2009;29(2):321-37. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

5. Ye S-M, Johnson RW. Regulation of interleukin-6 gene expression in brain of aged mice by nuclear factor κB. J Neuroimmunol. 2001;117(1-2):87-96. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

6. Viviani B, Boraso M. Cytokines and neuronal channels: a molecular basis for age-related decline of neuronal function? Exp Gerontol. 2011;46(2-3):199-206. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

7. Lucas S-M, Rothwell NJ, Gibson RM. The role of inflammation in CNS injury and disease. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147(S1):S232-S40. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

8. Capuron L, Miller AH. Immune system to brain signaling: neuropsychopharmacological implications. Pharmacol Ther. 2011;130(2):226-38. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

9. Erickson KI, Voss MW, Prakash RS, Basak C, Szabo A, Chaddock L, et al. Exercise training increases size of hippocampus and improves memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(7):3017-22. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

10. Hill RD, Storandt M, Malley M. The impact of long-term exercise training on psychological function in older adults. J Gerontol. 1993;48(1):P12-P7. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

11. Archer T. Physical exercise alleviates debilities of normal aging and Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neurol Scand. 2011;123(4):221-38. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

12. Archer T, Fredriksson A, Johansson B. Exercise alleviates Parkinsonism: clinical and laboratory evidence. Acta Neurol Scand. 2011;123(2):73-84. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

13. Atakan MM, Li Y, Koşar ŞN, Turnagöl HH, Yan X. Evidence-based effects of high-intensity interval training on exercise capacity and health: A review with historical perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(13):7201. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

14. Tondpa KB, Dehkhoda MR, AMANI SS. Improvement of aerobic power and health status in overweight patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with high intensity interval training. Payavard Salamat Year:2019;13(1):71-80. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

15. Muscella A, Stefàno E, Marsigliante S. The effects of exercise training on lipid metabolism and coronary heart disease. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2020;319(1):H76-H88. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

16. Iaccarino G, Franco D, Sorriento D, Strisciuglio T, Barbato E, Morisco C. Modulation of insulin sensitivity by exercise training: implications for cardiovascular prevention. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2021;14(2):256-70. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

17. Khajehlandi M, Bolboli L, Siahkuhian M, Rami M, Tabandeh M, Khoramipour K, et al. Endurance training regulates expression of some angiogenesis-related genes in cardiac tissue of experimentally induced diabetic rats. Biomolecules. 2021;11(4):498. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

18. Wang B, Zhao C, Wang Y, Tian X, Lin J, Zhu B, et al. Exercise ameliorating myocardial injury in type 2 diabetic rats by inhibiting excessive mitochondrial fission involving increased irisin expression and AMP‐activated protein kinase phosphorylation. J Diabetes. 2024;16(1):e13475. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

19. Zhang F, Lin JJ, Tian Hn, Wang J. Effect of exercise on improving myocardial mitochondrial function in decreasing diabetic cardiomyopathy. Exp Physiol. 2024;109(2):190-201. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

20. Freitas DA, Rocha-Vieira E, De Sousa RAL, Soares BA, Rocha-Gomes A, Garcia BCC, et al. High-intensity interval training improves cerebellar antioxidant capacity without affecting cognitive functions in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2019;376:112181. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

21. Freitas DA, Rocha-Vieira E, Soares BA, Nonato LF, Fonseca SR, Martins JB, et al. High intensity interval training modulates hippocampal oxidative stress, BDNF and inflammatory mediators in rats. Physiol Behav. 2018;184:6-11. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

22. Zwetsloot KA, John CS, Lawrence MM, Battista RA, Shanely RA. High-intensity interval training induces a modest systemic inflammatory response in active, young men. J Inflamm Res. 2014:7:9-17. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

23. Nichol KE, Poon WW, Parachikova AI, Cribbs DH, Glabe CG, Cotman CW. Exercise alters the immune profile in Tg2576 Alzheimer mice toward a response coincident with improved cognitive performance and decreased amyloid. J Neuroinflammation.2008:5:13. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

24. Katar M, Gevrek F. Relation of the intense physical exercise and asprosin concentrations in type 2 diabetic rats. Tissue Cell. 2024;90:102501. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

25. Aydin S, Kilinc F, Ugur K, Aydin MA, Yalcin MH, Kuloglu T, et al. Effects of irisin and exercise on adropin and betatrophin in a new metabolic syndrome model. Biotech Histochem. 2024;99(1):21-32. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

26. Soori R, Amini AA, Choobineh S, Eskandari A, Behjat A, Ghram A, et al. Exercise attenuates myocardial fibrosis and increases angiogenesis-related molecules in the myocardium of aged rats. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2022;128(1):1-6. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

27. Zhang B, Bailey WM, Braun KJ, Gensel JC. Age decreases macrophage IL-10 expression: implications for functional recovery and tissue repair in spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 2015;273:83-91. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

28. Sellami M, Bragazzi NL, Aboghaba B, Elrayess MA. The impact of acute and chronic exercise on immunoglobulins and cytokines in elderly: insights from a critical review of the literature. Front Immunol. 2021;12:631873. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

29. Herbert P, Hayes LD, Sculthorpe N, Grace FM. High-intensity interval training (HIIT) increases insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) in sedentary aging men but not masters' athletes: an observational study. Aging Male. 2017;20(1):54-9. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

30. Ebrahimnezhad N, Nayebifar S, Soltani Z, Khoramipour K. High-intensity interval training reduced oxidative stress and apoptosis in the hippocampus of male rats with type 2 diabetes: The role of the PGC1α-Keap1-Nrf2 signaling pathway. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2023;26(11):1313-9. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

31. Naseri A, Naseri A. The effect of a swimming training course on memory and IL-6 level in the Hippocampus and Prefrontal Cortex of Mice with Traumatic Brain Injury. Journal of Sports and Biomotor Sciences. 2023;15(29):43-53. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

32. Signorelli SS, Mazzarino MC, Pino LD, Malaponte G, Porto C, Pennisi G, et al. High circulating levels of cytokines (IL-6 and TNFa), adhesion molecules (VCAM-1 and ICAM-1) and selectins in patients with peripheral arterial disease at rest and after a treadmill test. Vasc Med. 2003;8(1):15-9. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

33. Beavers KM, Hsu F-C, Isom S, Kritchevsky SB, Church T, Goodpaster B, et al. Long-term physical activity and inflammatory biomarkers in older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(12):2189-96. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

34. Shargh Z, Asghari K, Asghariehahari M, Chodari L. Combined effect of exercise and curcumin on inflammation-associated microRNAs and cytokines in old male rats: A promising approach against inflammaging. Heliyon. 2025;11(2):e41895. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

35. Goldhammer E, Tanchilevitch A, Maor I, Beniamini Y, Rosenschein U, Sagiv M. Exercise training modulates cytokines activity in coronary heart disease patients. Int J Cardiol. 2005;100(1):93-9. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

36. Abbasi M, Kordi M, Daryanoosh F. The effect of eight weeks of high-intensity interval swimming training on the expression of PGC-1α and IL-6 proteins and memory function in brain hippocampus in rats with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis induced by high fat diet. Journal of Applied Health Studies in Sport Physiology. 2023. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

37. Tir AMD, Labor M, Plavec D. The effects of physical activity on chronic subclinical systemic inflammation. Arh Hig Rada Toksikol. 2017;68(4):276-86. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

38. Scisciola L, Fontanella RA, Surina, Cataldo V, Paolisso G, Barbieri M. Sarcopenia and cognitive function: role of myokines in muscle brain cross-talk. Life. 2021;11(2):173. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

39. Ren Z, Yang M, Guan Z, Yu W. Astrocytic α7 nicotinic receptor activation inhibits amyloid-β aggregation by upregulating endogenous αB-crystallin through the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2019;16(1):39-48. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

40. Petersen AMW, Pedersen BK. The anti-inflammatory effect of exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98(4):1154-62. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

41. Hamada K, Vannier E, Sacheck JM, Witsell AL, Roubenoff R. Senescence of human skeletal muscle impairs the local inflammatory cytokine response to acute eccentric exercise. FASEB J. 2005;19(2):264-6. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

42. Buford TW, Cooke MB, Willoughby DS. Resistance exercise-induced changes of inflammatory gene expression within human skeletal muscle. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2009;107(4):463-71. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

43. Naderi A, Saremi A, Afarinesh Khaki MR. Investigation of the Effect of 12 Weeks of Endurance Training and Sumac Intake on the Serum Levels of Nitric Oxide and Interleukin-1 Beta in Male Rats with Alzheimer's. cmja. 2024,14(1):29-37. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

44. Pourahmad J, Eskandari MR, Shakibaei R, Kamalinejad M. A search for hepatoprotective activity of aqueous extract of Rhus coriaria L. against oxidative stress cytotoxicity. Food Chem Toxicol. 2010;48(3):854-8. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

45. Puoyan-Majd S, Parnow A, Rashno M, Heidarimoghadam R, Komaki A. The Protective Effects of High-Intensity Interval Training Combined with Q10 Supplementation on Learning and Memory Impairments in Male Rats with Amyloid-β-Induced Alzheimer's Disease. J Alzheimers Dis.

2024;99(s1):S67-S80. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

46. Broderick TL, Sennott JM, Gutkowska J, Jankowski M. Anti-inflammatory and angiogenic effects of exercise training in cardiac muscle of diabetic mice. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2019:565-73. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

47. Sarikhani P, Gaeini AA, Ravasi AA. The effect of vitamin D catabolism supplementation and very intense intermittent exercise on some systemic indices (IL-1b and beta-catenin) of heart tissue in middle-aged Wistar males. Sport Physiology & Management Investigations. 2025;17(1):55-73. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

48. Wang L, Lavier J, Hua W, Wang Y, Gong L, Wei H, et al. High-intensity interval training and moderate-intensity continuous training attenuate oxidative damage and promote myokine response in the skeletal muscle of ApoE KO mice on high-fat diet. Antioxidants. 2021;10(7):992. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

49. Lu Z, Xu Y, Song Y, Bíró I, Gu Y. A mixed comparisons of different intensities and types of physical exercise in patients with diseases related to oxidative stress: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Front Physiol. 2021;12:700055. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

50. Rami M, Rahdar S, Ahmadi Hekmatikar A, Awang Daud DM. Highlighting the novel effects of high-intensity interval training on some histopathological and molecular indices in the heart of type 2 diabetic rats. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1175585. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

51. Barzegar H, Vosadi E, Borjian Fard M. The Effect of Different Modes of Training on Plasma Levels of IL-6 and IL-10 in Male Mature Wistar Rats. Journal of Sport Biosciences. 2017;9(2):171-81. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

52. Dorneles GP, Haddad DO, Fagundes VO, Vargas BK, Kloecker A, Romão PRT, et al. High intensity interval exercise decreases IL-8 and enhances the immunomodulatory cytokine interleukin-10 in lean and overweight-obese individuals. Cytokine. 2016;77:1-9. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

53. Amidei C, Sole ML. Physiological responses to passive exercise in adults receiving mechanical ventilation. Am J Crit Care. 2013;22(4):337-48. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

54. Nicklas BJ, Hsu FC, Brinkley TJ, Church T, Goodpaster BH, Kritchevsky SB, et al. Exercise training and plasma C‐reactive protein and interleukin‐6 in elderly people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(11):2045-52. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

55. Aksoy Y, Yapanoğlu T, Aksoy H, Demircan B, Öztaşan N, Canakci E, et al. Effects of endurance training on antioxidant defense mechanisms and lipid peroxidation in testis of rats. Arch Androl. 2006;52(4):319-23. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |

.PNG)

.PNG)