Volume 13, Issue 2 (5-2025)

Jorjani Biomed J 2025, 13(2): 20-28 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rahmati M, Arabfard M. Comparative performance of machine learning models in ischemic stroke classification. Jorjani Biomed J 2025; 13 (2) :20-28

URL: http://goums.ac.ir/jorjanijournal/article-1-1052-en.html

URL: http://goums.ac.ir/jorjanijournal/article-1-1052-en.html

1- Pasteur Institute of Iran, Tehran, Iran

2- Artificial Intelligence in Health Research Center, Biomedicine Technologies Institute, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran ,arabfard@gmail.com

2- Artificial Intelligence in Health Research Center, Biomedicine Technologies Institute, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran ,

Keywords: Ischemic Stroke, Machine Learning, Random Forest, Predictive Medicine, K-Nearest Neighbors

Full-Text [PDF 1119 kb]

(385 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2626 Views)

The KNN model was applied to classify the data based on nearest-neighbor distances (16,17). The model’s performance was evaluated using accuracy, precision, specificity, and sensitivity rates, confidence values, and AUC/Gini AUC scores, as described previously (18). Confidence thresholds were analyzed to optimize classification reliability.

The dataset was partitioned using the Holdout method, with 70% of the data used for training and 30% for testing. This approach was chosen to ensure a robust evaluation of model performance while maintaining a sufficient sample size for both training and testing. For the KNN algorithm, the value of k was set to 5 based on preliminary experiments that showed optimal performance at this value. Multiple experiments were conducted using values of k ranging from 3 to 10, and k=5 was selected as it provided the best balance between accuracy and computational efficiency.

We selected Random Forest, CHAID, and KNN for their unique strengths in stroke prediction. Random Forest was chosen for its high accuracy and ability to handle large datasets with many features. CHAID was selected for its interpretability, as it generates decision trees that can be easily understood by clinicians. KNN was included for its simplicity and effectiveness in classifying data based on nearest neighbors, which is particularly useful for small datasets.

Results

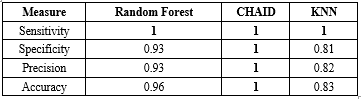

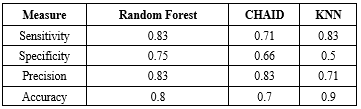

The results obtained from the algorithms are as follows. All models were developed using both training and testing data, with the dataset split into two segments: 70% for training and 30% for testing. The evaluation metrics for the data mining models for the training and test data are presented in Table 1 and 2. The Random Forest model demonstrated exceptional performance, achieving an accuracy of 96.67% in the training partition and 80% in the testing partition. This represents a significant improvement over previous studies using similar datasets, where accuracy typically ranged between 70-85%. The CHAID algorithm also showed strong performance with 100% accuracy in training and 70% in testing, while the KNN model achieved 83.33% accuracy in training and 90% in testing. These findings highlight the need for larger datasets and cross-validation techniques to improve model generalizability.

Enrichment analysis and biological pathways

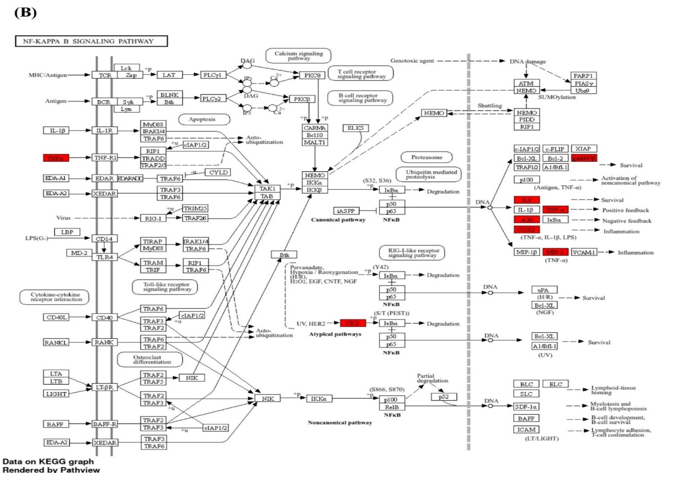

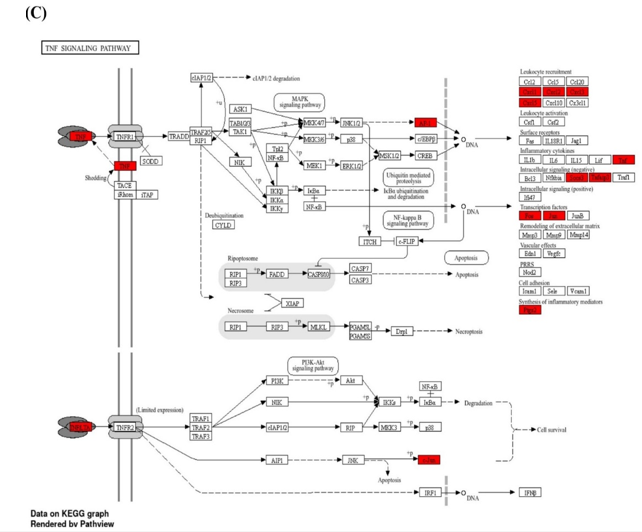

We conducted gene enrichment analysis on the 414 significant genes identified during feature selection. Gene enrichment analysis is illustrated in Figure 1. The majority of the identified genes are associated with inflammatory and immune responses, including the IL-17, NF-κB, and TNF signaling pathways. According to the KEGG database results, these biological pathways are presented in Figures 2A - C.

Random forest classification

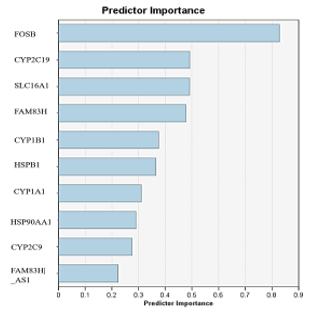

The decision rules represent conditions that define the categories or groups within the classification model. Each rule consists of one or more predictor variables and corresponding threshold values. Figure 3 shows genes identified as important predictors for ischemic stroke. These genes include: FOSB, CYP2C19, SLC16A1, FAM83H, CYP1B1, HSPB1, CYP1A1, HSP90AA1, CYP2C9, and FAM83H-AS1.

In the training partition, the model achieved an accuracy of 96.67%, correctly classifying 29 out of 30 cases. In the testing partition, it achieved an accuracy of 80%, correctly classifying all 8 cases. The training partition results yielded an AUC score of 0.973 and a Gini AUC score of 0.946. In the testing partition, the model achieved an AUC score of 0.917 and a Gini AUC score of 0.833.

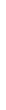

The decision tree generated by the CHAID algorithm contains six nodes. Node 0, the root node, represents the entire dataset of 30 cases, with 53.333% (16 cases) in the “control” category and 46.667% (14 cases) in the “case” category. Node 1 results from splitting the root node based on TP53. The split criterion TP53 ≤ 6.336 assigns all cases with values less than or equal to 6.336 to this node. It contains 9 cases, all in the “case” category (100%). Node 2 also results from splitting the root node on TP53. The split criterion TP53 > 6.336 assigns all cases with values greater than 6.336 to this node, which includes 21 cases, with 76.190% (16 cases) in “control” and 23.810% (5 cases) in “case.”

Moreover, node 3 results from splitting Node 2 based on CYP2D6. The split criterion CYP2D6 ≤ 4.950 assigns all cases with values less than or equal to 4.950 to this node. It contains 4 cases, all in the “case” category (100%). Node 4 results from splitting Node 2 based on CYP2D6 > 4.950, with 17 cases, 94.118% (16 cases) in “control” and 5.882% (1 case) in “case.” Node 5 results from splitting Node 4 based on CYP1A1 ≤ 12.804, assigning all cases with values ≤ 12.804 to this node, containing 16 cases-all “control” (100%). Node 6 results from splitting Node 4 based on CYP1A1 > 12.804, containing one case, classified as “case” (100%).

KNN model

The KNN model demonstrated strong performance across the data partitions. In the training partition, the model achieved an accuracy of 83.33%, correctly classifying 25 out of 30 cases. In the testing partition, it achieved an accuracy of 90%, correctly classifying all 9 cases. The AUC for the training partition was 0.904 with a Gini AUC score of 0.808. In the testing partition, the AUC was 0.854 and the Gini AUC was 0.708.

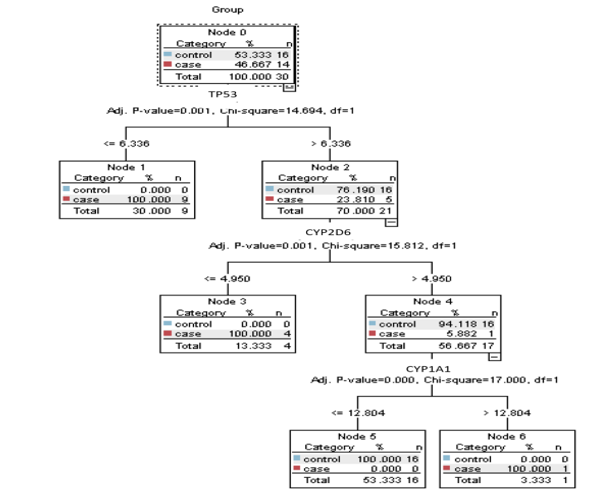

Overall, the KNN model exhibited strong performance, characterized by high accuracy, AUC, and Gini AUC scores in both training and testing partitions. Additionally, we identified three genes-RPLP0, Paxillin, and HSP90AA1-as significant predictors for ischemic stroke diagnosis. Figure 5 illustrates the performance metrics and associated confidence intervals for the KNN model across different partitions, including accuracy rates, confidence ranges, and AUC/Gini AUC scores, highlighting the model’s overall efficacy and areas for potential improvement.

Discussion

Despite advances in medical care and preventive measures in high-income countries, the overall incidence of stroke remains a substantial concern due to an aging population and associated risk factors (19). Given the limitations of current diagnostic methods, supplementary tools that provide timely and accurate information at the molecular level are increasingly necessary. Our findings advance previous research by demonstrating the effectiveness of RNA-seq data combined with machine learning models for ischemic stroke classification. Unlike traditional approaches that rely on neuroimaging, our method offers a molecular-level understanding of stroke pathology, identifying key genes (Such as TP53, CYP1A1, CYP2D6) and pathways (Including IL-17, NF-κB, and TNF signaling) that are typically not captured by imaging techniques. The identification of these pathways has important therapeutic implications, as they are central regulators of inflammatory and immune responses-critical components of ischemic stroke pathology. Targeting these pathways with anti-inflammatory agents or immunomodulators may provide new treatment opportunities that could improve clinical outcomes.

Recent advancements in genomics and bioinformatics have facilitated the discovery of novel biomarkers for stroke diagnosis and prognosis (20). These biomarkers, identified through high-throughput techniques such as RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), offer the potential for earlier detection and a deeper understanding of stroke pathophysiology (21). Parallel developments in machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) have introduced new strategies for enhancing diagnostic accuracy and treatment planning (22,23). These computational approaches can analyze large and complex datasets, identify subtle patterns, and produce predictions that may not be readily apparent through traditional statistical methods. ML algorithms, including Random Forests and KNN, have shown promise in medical applications such as stroke prediction and classification (24,25).

Machine learning has emerged as a transformative tool in medical research, particularly for analyzing complex data such as RNA-seq (26). ML algorithms can be used to classify stroke types, predict outcomes, and identify novel biomarkers by analyzing gene expression patterns and related features. The application of ML in stroke research provides several advantages. ML models can process large volumes of data and detect complex relationships that may be missed by traditional methods-an especially valuable capability given the high-dimensional nature of transcriptomic datasets (27). These models can be trained to predict stroke occurrence, severity, and outcomes using gene expression profiles, supporting early diagnosis and enabling personalized treatment strategies (28). ML methods also aid in dimensionality reduction, preserving essential biological information while improving model performance (29). Furthermore, ML models can integrate multi-omics data-such as genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics-to provide a more comprehensive understanding of stroke pathology and identify therapeutic targets (30).

In this study, enrichment analyses (Figures 1 and 2) showed that the most prominent pathways were associated with inflammatory responses. We developed and validated several ML models using RNA-seq data to predict ischemic stroke, including Random Forest Classification, the CHAID Algorithm, and KNN. Each model offered unique insights into stroke prediction and classification, highlighting their specific strengths and limitations.

The Random Forest Classification model is a decision tree-based ensemble algorithm that builds multiple trees and aggregates their outputs to improve predictive accuracy (31). In our study, this model demonstrated exceptional performance, achieving 96.67% accuracy in the training set and 80% in the test set. The decision rules effectively classified stroke patients and controls based on gene expression thresholds. For example, certain rules indicated that high FOSB expression and low FAM83H-AS1 expression were associated with stroke. These findings are biologically plausible, as FOSB, a transcription factor, plays roles in cell proliferation, differentiation, inflammatory responses, and neuronal plasticity (32,33). FAM83H, while primarily known for its involvement in enamel formation (34), may influence inflammation or gene regulation, suggesting a possible role in stroke mechanisms.

The CHAID algorithm produced a decision tree with six nodes based on statistically significant splits (15). The model achieved perfect accuracy in the training set and moderate-high performance in the testing set. The CHAID tree identified TP53, CYP1A1, and CYP2D6 as critical predictors. TP53 is a central regulator of apoptosis, inflammation, cell cycle progression, and DNA repair, making it highly relevant to ischemic injury and neuroprotection (35). CYP1A1, whose expression can be regulated by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) and p53 pathways, may participate in oxidative metabolism and cellular responses to ischemia (36). CYP2D6, a major drug-metabolizing enzyme, may influence inflammatory processes or treatment responses in stroke patients (37,38). These genes therefore represent meaningful biological markers for classification.

The KNN model classifies samples based on similarity in the feature space (39). It demonstrated strong performance with high accuracy across training and testing partitions. The model identified RPLP0, Paxillin, and HSP90AA1 as significant predictors. RPLP0, a ribosomal protein involved in protein synthesis, may contribute to neuronal repair, though direct evidence in stroke is limited (40). Paxillin is involved in endothelial migration, inflammation, and vascular smooth muscle regulation-processes central to ischemic stroke pathology (41-43). HSP90AA1, a molecular chaperone, promotes neuroprotection, modulates inflammation, and may serve as a biomarker for stroke outcomes (42,44).

Overall, the ML models demonstrated strong potential for stroke prediction and classification. Each model offered distinct advantages. Random Forest provided clear and interpretable decision rules with high accuracy. The CHAID algorithm offered transparent decision paths based on statistical significance. KNN delivered strong predictive performance with high accuracy and confidence values. While KNN and Random Forest are computationally more demanding, all three models contribute unique perspectives on stroke prediction. The choice of model ultimately depends on research needs such as interpretability, accuracy, and computational resources. Combining multiple models could further improve predictive performance and offer more comprehensive assessments of stroke risk. Our findings align with previous studies that have used ML for stroke prediction, but our integration of RNA-seq data adds a novel molecular-level dimension.

Despite promising results, this study has limitations. The dataset consisted of only 40 samples (20 stroke patients and 20 controls), which may limit generalizability and statistical power. Additionally, model evaluation relied on a single train-test split without repeated randomization or cross-validation, which may introduce sampling bias and overestimate performance. Although our feature selection was focused on biologically relevant genes, incorporating additional omics data or clinical variables could improve predictive accuracy. Future research should validate these findings in larger, independent cohorts using rigorous validation methods such as k-fold cross-validation, and explore integrating molecular signatures into clinical workflows to support real-world diagnostic and therapeutic decision-making.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated the potential of machine learning techniques, including Random Forest Classification, the CHAID Algorithm, and K-Nearest Neighbors, in predicting and classifying ischemic stroke using RNA-seq data. Each model offered unique insights and strengths, highlighting the importance of ML in advancing stroke diagnosis and treatment. While the results are promising, further research and optimization are needed to enhance model performance and demonstrate their practical integration into clinical workflows.

The findings suggest that combining genomic data with advanced computational techniques can enable earlier detection and a deeper understanding of ischemic stroke mechanisms. Future studies should expand the dataset and incorporate additional omics layers to improve model robustness and generalizability. Ultimately, the application of ML in stroke research holds significant promise for improving diagnostic accuracy and personalizing treatment strategies, paving the way for more effective stroke management and better patient outcomes.

Acknowledgement

We sincerely thank Ms. Nahid Nemati and Mr. Hossein Hosseini, Ph.D. candidates in Systems Biomedicine at the Pasteur Institute of Iran, for their invaluable support and contributions.

Funding sources

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical statement

This study did not involve human participants, animals, or biological samples; therefore, ethical approval was not required.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest relevant to this study.

Author contributions

Mina Rahmati: Data preprocessing, machine learning modeling, and drafting the manuscript. Masoud Arabfard: Supervision, statistical analysis, model evaluation, and manuscript revision. Both authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability statement

The raw RNA-seq gene expression data utilized in this study are publicly accessible in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository under the accession number GSE22255. The analyzed datasets and associated computational findings are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author, Masoud Arabfard.

Full-Text: (29 Views)

Introduction

Stroke is a major cause of disability in adults and the second leading cause of death worldwide, significantly impacting individuals and healthcare systems (1). Over the past thirty years, the incidence and prevalence of stroke have risen, influenced by demographic and economic factors (2). Ischemic strokes, which occur when blood flow is blocked by an occluded blood vessel, represent about 87% of cases (3). Hemorrhagic strokes, resulting from the rupture or leakage of weakened blood vessels in the brain, account for the remaining 13% (4). In high-income countries, stroke incidence has declined due to improved preventive measures and lifestyle changes, but an aging population is expected to increase new cases, adding to the healthcare burden (5). Given the severity and prevalence of strokes, there is growing interest in using novel biomarkers as supplementary diagnostic tools to enhance the accuracy of routine techniques (3). Current diagnostic tools, primarily neuroimaging techniques, though essential, have limitations, including high costs, limited availability, and delays in detection, especially in the early stages of stroke (6). These limitations highlight the importance of searching for novel biomarkers that can provide more timely and accurate diagnoses, monitor disease severity, and assess treatment efficacy (7). Recent advancements in genomics and bioinformatics have led to the exploration of RNA-seq data as a powerful tool for identifying such biomarkers, offering a molecular-level understanding of stroke pathology that complements traditional diagnostic methods. Unlike proteomics or metabolomics, which focus on proteins and metabolites, RNA-seq provides a comprehensive view of gene expression, allowing for the identification of differentially expressed genes and pathways that may be involved in stroke pathology.

RNA-seq data analysis poses significant challenges, including complex preprocessing steps such as quality control, alignment, and normalization, all of which critically impact the results. The high dimensionality of transcriptomic data, with thousands of genes across limited samples, complicates feature selection and increases the risk of overfitting, while large sequencing volumes demand scalable computational resources. Machine learning (ML) offers solutions by automating preprocessing and improving reproducibility through adaptive pipelines. Scalable ML frameworks enable efficient processing of large datasets, and integrating ML enhances accuracy and biological insight. Thus, ML addresses RNA-seq challenges by optimizing analysis robustness and interpretability in transcriptomic studies.

Extensive studies on stroke utilize large datasets, offering valuable insights into real-world practices and enabling population-based analyses. However, these datasets often have limitations, including potential inaccuracies in ICD-10 diagnostic codes, which may be influenced by physician diagnostic precision and financial incentives (3). Recently, artificial intelligence (AI) has gained significant popularity, particularly in the fields of ML and deep learning (DL) (8). Researchers have established and validated operational definitions of stroke, developing algorithms to diagnose ischemic strokes using claims data and multicenter registries. ML has become a powerful tool in stroke research, enabling the classification of stroke types, prediction of outcomes, and identification of subtypes (9). These techniques allow for the analysis of large datasets, recognition of patterns, and enhancement of diagnostic, treatment, and prognostic capabilities for stroke patients (10,11).

AI, particularly ML and DL, is crucial for stroke diagnosis due to its ability to rapidly analyze complex medical data with high accuracy. Unlike traditional methods, which rely on manual interpretation and can be time-consuming, ML algorithms detect subtle patterns and early indicators of stroke that may be missed by human clinicians. ML models can also continuously learn from new data, enhancing their predictive performance over time. These advantages lead to faster, more precise diagnoses, ultimately improving patient outcomes and reducing healthcare burdens.

Combining ML with RNA-seq revolutionizes stroke diagnosis by detecting novel biomarkers and gene-expression patterns that traditional methods may overlook. This data-driven approach enhances diagnostic precision and provides real-time molecular insights for personalized treatment. ML models uncover hidden transcriptomic signatures, enabling early intervention and optimized therapies. By bridging molecular biology and clinical practice, this synergy improves patient outcomes. The research represents a major leap forward in precision medicine for stroke care. This study aims to apply and validate a machine learning-based predictive model for ischemic stroke using RNA-seq data. By analyzing gene expression profiles from stroke patients and healthy controls, and selecting significant genes, we seek to improve stroke diagnosis accuracy and contribute to more effective treatment strategies. Our work builds on previous research by leveraging RNA-seq data, which provides a more comprehensive view of gene expression compared to traditional methods, and by comparing multiple machine learning models to identify the most effective approach for stroke classification.

Methods

Data acquisition

We obtained RNA-seq data from the GEO database, specifically from the study conducted by Tiago Krug and colleagues in 2012 (GEO Accession: GSE22255) (12). This dataset includes expression profiles of 54,676 genes across 20 stroke patients and 20 control samples.

Model preparation

We developed a predictive model for ischemic stroke using machine learning techniques, leveraging a dataset of 54,677 features from Tiago Krug's research, including a “Group” feature that categorizes samples as either healthy or patient. Using IBM SPSS Modeler version 18 (IBM Corporation, USA), we performed feature selection to focus on 414 significant genes, thereby enhancing model performance and reducing computational complexity. To identify the most biologically relevant genes for stroke diagnosis, we selected 414 genes that met our threshold criteria: a P-Value < 0.05 (Indicating statistical significance) and a fold change > 2 (Representing substantial differential expression). This dual-threshold approach ensured that we focused on genes showing both statistically reliable and biologically meaningful expression changes in stroke. The selected 414 genes represent the most promising transcriptomic markers for further machine learning analysis and potential clinical application. These genes were further analyzed using the Random Forest algorithm to identify the most relevant features for ischemic stroke classification. Preprocessing steps included normalization of gene expression data using the TPM (Transcripts Per Million) method and handling missing values using the k-nearest neighbors imputation algorithm.

Gene enrichment analysis

Gene enrichment analysis was performed using the Gene Ontology (GO) and KEGG databases to identify overrepresented biological processes and pathways associated with ischemic stroke. Statistical significance was assessed using hypergeometric tests, with p-values adjusted for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. The results were visualized through bar plots to illustrate enriched terms and pathways, providing insights into the biological relevance of our selected gene set. This step helps contextualize the selected genes within broader biological mechanisms, offering deeper insights into the underlying pathology of stroke.

Classification algorithms and rationale selection

Random Forest (RF)

A supervised ensemble learning method that constructs multiple decision trees during training and outputs the mode (Classification) or mean (Regression) of individual predictions. RF improves accuracy by reducing overfitting through bagging (Bootstrap aggregating) and random feature selection. Its robustness to high-dimensional data (e.g., RNA-seq’s thousands of genes) and ability to rank feature importance make it ideal for biomarker discovery and stroke subtype classification.

CHAID (Chi-squared Automatic Interaction Detector)

A decision tree algorithm that uses chi-square tests to identify optimal splits in categorical or discretized continuous variables. CHAID excels in identifying hierarchical interactions between features (e.g., gene-gene or gene-clinical variable relationships), providing interpretable rules for stroke risk stratification. Unlike RF, CHAID is non-parametric and handles multi-way splits, aiding clinical decision-making with transparent criteria.

K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN)

A lazy, instance-based learning algorithm that classifies samples by majority vote of the k nearest neighbors in feature space. KNN’s simplicity and adaptability to non-linear patterns suit RNA-seq data, where local gene expression similarities may define stroke phenotypes. However, its performance depends on optimal distance metrics (e.g., Euclidean, Manhattan) and parameter tuning (K-selection), and it requires careful normalization due to sensitivity to feature scales.

Rationale for selection

The selected machine learning algorithms were chosen for their complementary strengths and in consultation with an expert in RNA-seq data analysis for stroke diagnosis. RF handles high dimensionality, CHAID offers interpretability for clinical translation, and KNN captures local expression patterns. Together, they address RNA-seq challenges (Noise, sparsity, volume) while enhancing stroke diagnostic precision beyond traditional statistical methods.

Model implementation and performance evaluation

We utilized a Random Forest Classification model to derive decision rules based on gene expression thresholds (10,11). The decision rules were formulated to classify samples into stroke patients or healthy controls. Each rule’s accuracy was assessed, and overall model accuracy was determined. The rules and their performance metrics are detailed in Table 1.

Stroke is a major cause of disability in adults and the second leading cause of death worldwide, significantly impacting individuals and healthcare systems (1). Over the past thirty years, the incidence and prevalence of stroke have risen, influenced by demographic and economic factors (2). Ischemic strokes, which occur when blood flow is blocked by an occluded blood vessel, represent about 87% of cases (3). Hemorrhagic strokes, resulting from the rupture or leakage of weakened blood vessels in the brain, account for the remaining 13% (4). In high-income countries, stroke incidence has declined due to improved preventive measures and lifestyle changes, but an aging population is expected to increase new cases, adding to the healthcare burden (5). Given the severity and prevalence of strokes, there is growing interest in using novel biomarkers as supplementary diagnostic tools to enhance the accuracy of routine techniques (3). Current diagnostic tools, primarily neuroimaging techniques, though essential, have limitations, including high costs, limited availability, and delays in detection, especially in the early stages of stroke (6). These limitations highlight the importance of searching for novel biomarkers that can provide more timely and accurate diagnoses, monitor disease severity, and assess treatment efficacy (7). Recent advancements in genomics and bioinformatics have led to the exploration of RNA-seq data as a powerful tool for identifying such biomarkers, offering a molecular-level understanding of stroke pathology that complements traditional diagnostic methods. Unlike proteomics or metabolomics, which focus on proteins and metabolites, RNA-seq provides a comprehensive view of gene expression, allowing for the identification of differentially expressed genes and pathways that may be involved in stroke pathology.

RNA-seq data analysis poses significant challenges, including complex preprocessing steps such as quality control, alignment, and normalization, all of which critically impact the results. The high dimensionality of transcriptomic data, with thousands of genes across limited samples, complicates feature selection and increases the risk of overfitting, while large sequencing volumes demand scalable computational resources. Machine learning (ML) offers solutions by automating preprocessing and improving reproducibility through adaptive pipelines. Scalable ML frameworks enable efficient processing of large datasets, and integrating ML enhances accuracy and biological insight. Thus, ML addresses RNA-seq challenges by optimizing analysis robustness and interpretability in transcriptomic studies.

Extensive studies on stroke utilize large datasets, offering valuable insights into real-world practices and enabling population-based analyses. However, these datasets often have limitations, including potential inaccuracies in ICD-10 diagnostic codes, which may be influenced by physician diagnostic precision and financial incentives (3). Recently, artificial intelligence (AI) has gained significant popularity, particularly in the fields of ML and deep learning (DL) (8). Researchers have established and validated operational definitions of stroke, developing algorithms to diagnose ischemic strokes using claims data and multicenter registries. ML has become a powerful tool in stroke research, enabling the classification of stroke types, prediction of outcomes, and identification of subtypes (9). These techniques allow for the analysis of large datasets, recognition of patterns, and enhancement of diagnostic, treatment, and prognostic capabilities for stroke patients (10,11).

AI, particularly ML and DL, is crucial for stroke diagnosis due to its ability to rapidly analyze complex medical data with high accuracy. Unlike traditional methods, which rely on manual interpretation and can be time-consuming, ML algorithms detect subtle patterns and early indicators of stroke that may be missed by human clinicians. ML models can also continuously learn from new data, enhancing their predictive performance over time. These advantages lead to faster, more precise diagnoses, ultimately improving patient outcomes and reducing healthcare burdens.

Combining ML with RNA-seq revolutionizes stroke diagnosis by detecting novel biomarkers and gene-expression patterns that traditional methods may overlook. This data-driven approach enhances diagnostic precision and provides real-time molecular insights for personalized treatment. ML models uncover hidden transcriptomic signatures, enabling early intervention and optimized therapies. By bridging molecular biology and clinical practice, this synergy improves patient outcomes. The research represents a major leap forward in precision medicine for stroke care. This study aims to apply and validate a machine learning-based predictive model for ischemic stroke using RNA-seq data. By analyzing gene expression profiles from stroke patients and healthy controls, and selecting significant genes, we seek to improve stroke diagnosis accuracy and contribute to more effective treatment strategies. Our work builds on previous research by leveraging RNA-seq data, which provides a more comprehensive view of gene expression compared to traditional methods, and by comparing multiple machine learning models to identify the most effective approach for stroke classification.

Methods

Data acquisition

We obtained RNA-seq data from the GEO database, specifically from the study conducted by Tiago Krug and colleagues in 2012 (GEO Accession: GSE22255) (12). This dataset includes expression profiles of 54,676 genes across 20 stroke patients and 20 control samples.

Model preparation

We developed a predictive model for ischemic stroke using machine learning techniques, leveraging a dataset of 54,677 features from Tiago Krug's research, including a “Group” feature that categorizes samples as either healthy or patient. Using IBM SPSS Modeler version 18 (IBM Corporation, USA), we performed feature selection to focus on 414 significant genes, thereby enhancing model performance and reducing computational complexity. To identify the most biologically relevant genes for stroke diagnosis, we selected 414 genes that met our threshold criteria: a P-Value < 0.05 (Indicating statistical significance) and a fold change > 2 (Representing substantial differential expression). This dual-threshold approach ensured that we focused on genes showing both statistically reliable and biologically meaningful expression changes in stroke. The selected 414 genes represent the most promising transcriptomic markers for further machine learning analysis and potential clinical application. These genes were further analyzed using the Random Forest algorithm to identify the most relevant features for ischemic stroke classification. Preprocessing steps included normalization of gene expression data using the TPM (Transcripts Per Million) method and handling missing values using the k-nearest neighbors imputation algorithm.

Gene enrichment analysis

Gene enrichment analysis was performed using the Gene Ontology (GO) and KEGG databases to identify overrepresented biological processes and pathways associated with ischemic stroke. Statistical significance was assessed using hypergeometric tests, with p-values adjusted for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. The results were visualized through bar plots to illustrate enriched terms and pathways, providing insights into the biological relevance of our selected gene set. This step helps contextualize the selected genes within broader biological mechanisms, offering deeper insights into the underlying pathology of stroke.

Classification algorithms and rationale selection

Random Forest (RF)

A supervised ensemble learning method that constructs multiple decision trees during training and outputs the mode (Classification) or mean (Regression) of individual predictions. RF improves accuracy by reducing overfitting through bagging (Bootstrap aggregating) and random feature selection. Its robustness to high-dimensional data (e.g., RNA-seq’s thousands of genes) and ability to rank feature importance make it ideal for biomarker discovery and stroke subtype classification.

CHAID (Chi-squared Automatic Interaction Detector)

A decision tree algorithm that uses chi-square tests to identify optimal splits in categorical or discretized continuous variables. CHAID excels in identifying hierarchical interactions between features (e.g., gene-gene or gene-clinical variable relationships), providing interpretable rules for stroke risk stratification. Unlike RF, CHAID is non-parametric and handles multi-way splits, aiding clinical decision-making with transparent criteria.

K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN)

A lazy, instance-based learning algorithm that classifies samples by majority vote of the k nearest neighbors in feature space. KNN’s simplicity and adaptability to non-linear patterns suit RNA-seq data, where local gene expression similarities may define stroke phenotypes. However, its performance depends on optimal distance metrics (e.g., Euclidean, Manhattan) and parameter tuning (K-selection), and it requires careful normalization due to sensitivity to feature scales.

Rationale for selection

The selected machine learning algorithms were chosen for their complementary strengths and in consultation with an expert in RNA-seq data analysis for stroke diagnosis. RF handles high dimensionality, CHAID offers interpretability for clinical translation, and KNN captures local expression patterns. Together, they address RNA-seq challenges (Noise, sparsity, volume) while enhancing stroke diagnostic precision beyond traditional statistical methods.

Model implementation and performance evaluation

We utilized a Random Forest Classification model to derive decision rules based on gene expression thresholds (10,11). The decision rules were formulated to classify samples into stroke patients or healthy controls. Each rule’s accuracy was assessed, and overall model accuracy was determined. The rules and their performance metrics are detailed in Table 1.

|

Table 1. Assessment criteria for classification models using training data

Sensitivity, specificity, precision, and accuracy are reported for Random Forest, CHAID, and KNN models |

The KNN model was applied to classify the data based on nearest-neighbor distances (16,17). The model’s performance was evaluated using accuracy, precision, specificity, and sensitivity rates, confidence values, and AUC/Gini AUC scores, as described previously (18). Confidence thresholds were analyzed to optimize classification reliability.

The dataset was partitioned using the Holdout method, with 70% of the data used for training and 30% for testing. This approach was chosen to ensure a robust evaluation of model performance while maintaining a sufficient sample size for both training and testing. For the KNN algorithm, the value of k was set to 5 based on preliminary experiments that showed optimal performance at this value. Multiple experiments were conducted using values of k ranging from 3 to 10, and k=5 was selected as it provided the best balance between accuracy and computational efficiency.

We selected Random Forest, CHAID, and KNN for their unique strengths in stroke prediction. Random Forest was chosen for its high accuracy and ability to handle large datasets with many features. CHAID was selected for its interpretability, as it generates decision trees that can be easily understood by clinicians. KNN was included for its simplicity and effectiveness in classifying data based on nearest neighbors, which is particularly useful for small datasets.

Results

The results obtained from the algorithms are as follows. All models were developed using both training and testing data, with the dataset split into two segments: 70% for training and 30% for testing. The evaluation metrics for the data mining models for the training and test data are presented in Table 1 and 2. The Random Forest model demonstrated exceptional performance, achieving an accuracy of 96.67% in the training partition and 80% in the testing partition. This represents a significant improvement over previous studies using similar datasets, where accuracy typically ranged between 70-85%. The CHAID algorithm also showed strong performance with 100% accuracy in training and 70% in testing, while the KNN model achieved 83.33% accuracy in training and 90% in testing. These findings highlight the need for larger datasets and cross-validation techniques to improve model generalizability.

Enrichment analysis and biological pathways

We conducted gene enrichment analysis on the 414 significant genes identified during feature selection. Gene enrichment analysis is illustrated in Figure 1. The majority of the identified genes are associated with inflammatory and immune responses, including the IL-17, NF-κB, and TNF signaling pathways. According to the KEGG database results, these biological pathways are presented in Figures 2A - C.

Random forest classification

The decision rules represent conditions that define the categories or groups within the classification model. Each rule consists of one or more predictor variables and corresponding threshold values. Figure 3 shows genes identified as important predictors for ischemic stroke. These genes include: FOSB, CYP2C19, SLC16A1, FAM83H, CYP1B1, HSPB1, CYP1A1, HSP90AA1, CYP2C9, and FAM83H-AS1.

In the training partition, the model achieved an accuracy of 96.67%, correctly classifying 29 out of 30 cases. In the testing partition, it achieved an accuracy of 80%, correctly classifying all 8 cases. The training partition results yielded an AUC score of 0.973 and a Gini AUC score of 0.946. In the testing partition, the model achieved an AUC score of 0.917 and a Gini AUC score of 0.833.

|

Table 2. Assessment criteria for classification models using test data

Sensitivity, specificity, precision, and accuracy are reported for Random Forest, CHAID, and KNN models. |

The decision tree generated by the CHAID algorithm contains six nodes. Node 0, the root node, represents the entire dataset of 30 cases, with 53.333% (16 cases) in the “control” category and 46.667% (14 cases) in the “case” category. Node 1 results from splitting the root node based on TP53. The split criterion TP53 ≤ 6.336 assigns all cases with values less than or equal to 6.336 to this node. It contains 9 cases, all in the “case” category (100%). Node 2 also results from splitting the root node on TP53. The split criterion TP53 > 6.336 assigns all cases with values greater than 6.336 to this node, which includes 21 cases, with 76.190% (16 cases) in “control” and 23.810% (5 cases) in “case.”

Moreover, node 3 results from splitting Node 2 based on CYP2D6. The split criterion CYP2D6 ≤ 4.950 assigns all cases with values less than or equal to 4.950 to this node. It contains 4 cases, all in the “case” category (100%). Node 4 results from splitting Node 2 based on CYP2D6 > 4.950, with 17 cases, 94.118% (16 cases) in “control” and 5.882% (1 case) in “case.” Node 5 results from splitting Node 4 based on CYP1A1 ≤ 12.804, assigning all cases with values ≤ 12.804 to this node, containing 16 cases-all “control” (100%). Node 6 results from splitting Node 4 based on CYP1A1 > 12.804, containing one case, classified as “case” (100%).

.PNG) Figure 1. Gene enrichment analysis in ischemic stroke patients. Bar plots illustrate the enriched terms and pathways identified using the Gene Ontology (GO) and KEGG databases |

.PNG)  |

Figure 2. The most inflammatory signaling pathways from the KEGG database in ischemic stroke patients: IL-17 (A), NF-κB (B), and TNF (C) |

Figure 3. Important genes identified as ischemic stroke predictors |

KNN model

The KNN model demonstrated strong performance across the data partitions. In the training partition, the model achieved an accuracy of 83.33%, correctly classifying 25 out of 30 cases. In the testing partition, it achieved an accuracy of 90%, correctly classifying all 9 cases. The AUC for the training partition was 0.904 with a Gini AUC score of 0.808. In the testing partition, the AUC was 0.854 and the Gini AUC was 0.708.

Overall, the KNN model exhibited strong performance, characterized by high accuracy, AUC, and Gini AUC scores in both training and testing partitions. Additionally, we identified three genes-RPLP0, Paxillin, and HSP90AA1-as significant predictors for ischemic stroke diagnosis. Figure 5 illustrates the performance metrics and associated confidence intervals for the KNN model across different partitions, including accuracy rates, confidence ranges, and AUC/Gini AUC scores, highlighting the model’s overall efficacy and areas for potential improvement.

Discussion

Despite advances in medical care and preventive measures in high-income countries, the overall incidence of stroke remains a substantial concern due to an aging population and associated risk factors (19). Given the limitations of current diagnostic methods, supplementary tools that provide timely and accurate information at the molecular level are increasingly necessary. Our findings advance previous research by demonstrating the effectiveness of RNA-seq data combined with machine learning models for ischemic stroke classification. Unlike traditional approaches that rely on neuroimaging, our method offers a molecular-level understanding of stroke pathology, identifying key genes (Such as TP53, CYP1A1, CYP2D6) and pathways (Including IL-17, NF-κB, and TNF signaling) that are typically not captured by imaging techniques. The identification of these pathways has important therapeutic implications, as they are central regulators of inflammatory and immune responses-critical components of ischemic stroke pathology. Targeting these pathways with anti-inflammatory agents or immunomodulators may provide new treatment opportunities that could improve clinical outcomes.

Recent advancements in genomics and bioinformatics have facilitated the discovery of novel biomarkers for stroke diagnosis and prognosis (20). These biomarkers, identified through high-throughput techniques such as RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), offer the potential for earlier detection and a deeper understanding of stroke pathophysiology (21). Parallel developments in machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) have introduced new strategies for enhancing diagnostic accuracy and treatment planning (22,23). These computational approaches can analyze large and complex datasets, identify subtle patterns, and produce predictions that may not be readily apparent through traditional statistical methods. ML algorithms, including Random Forests and KNN, have shown promise in medical applications such as stroke prediction and classification (24,25).

Machine learning has emerged as a transformative tool in medical research, particularly for analyzing complex data such as RNA-seq (26). ML algorithms can be used to classify stroke types, predict outcomes, and identify novel biomarkers by analyzing gene expression patterns and related features. The application of ML in stroke research provides several advantages. ML models can process large volumes of data and detect complex relationships that may be missed by traditional methods-an especially valuable capability given the high-dimensional nature of transcriptomic datasets (27). These models can be trained to predict stroke occurrence, severity, and outcomes using gene expression profiles, supporting early diagnosis and enabling personalized treatment strategies (28). ML methods also aid in dimensionality reduction, preserving essential biological information while improving model performance (29). Furthermore, ML models can integrate multi-omics data-such as genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics-to provide a more comprehensive understanding of stroke pathology and identify therapeutic targets (30).

In this study, enrichment analyses (Figures 1 and 2) showed that the most prominent pathways were associated with inflammatory responses. We developed and validated several ML models using RNA-seq data to predict ischemic stroke, including Random Forest Classification, the CHAID Algorithm, and KNN. Each model offered unique insights into stroke prediction and classification, highlighting their specific strengths and limitations.

The Random Forest Classification model is a decision tree-based ensemble algorithm that builds multiple trees and aggregates their outputs to improve predictive accuracy (31). In our study, this model demonstrated exceptional performance, achieving 96.67% accuracy in the training set and 80% in the test set. The decision rules effectively classified stroke patients and controls based on gene expression thresholds. For example, certain rules indicated that high FOSB expression and low FAM83H-AS1 expression were associated with stroke. These findings are biologically plausible, as FOSB, a transcription factor, plays roles in cell proliferation, differentiation, inflammatory responses, and neuronal plasticity (32,33). FAM83H, while primarily known for its involvement in enamel formation (34), may influence inflammation or gene regulation, suggesting a possible role in stroke mechanisms.

The CHAID algorithm produced a decision tree with six nodes based on statistically significant splits (15). The model achieved perfect accuracy in the training set and moderate-high performance in the testing set. The CHAID tree identified TP53, CYP1A1, and CYP2D6 as critical predictors. TP53 is a central regulator of apoptosis, inflammation, cell cycle progression, and DNA repair, making it highly relevant to ischemic injury and neuroprotection (35). CYP1A1, whose expression can be regulated by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) and p53 pathways, may participate in oxidative metabolism and cellular responses to ischemia (36). CYP2D6, a major drug-metabolizing enzyme, may influence inflammatory processes or treatment responses in stroke patients (37,38). These genes therefore represent meaningful biological markers for classification.

The KNN model classifies samples based on similarity in the feature space (39). It demonstrated strong performance with high accuracy across training and testing partitions. The model identified RPLP0, Paxillin, and HSP90AA1 as significant predictors. RPLP0, a ribosomal protein involved in protein synthesis, may contribute to neuronal repair, though direct evidence in stroke is limited (40). Paxillin is involved in endothelial migration, inflammation, and vascular smooth muscle regulation-processes central to ischemic stroke pathology (41-43). HSP90AA1, a molecular chaperone, promotes neuroprotection, modulates inflammation, and may serve as a biomarker for stroke outcomes (42,44).

Overall, the ML models demonstrated strong potential for stroke prediction and classification. Each model offered distinct advantages. Random Forest provided clear and interpretable decision rules with high accuracy. The CHAID algorithm offered transparent decision paths based on statistical significance. KNN delivered strong predictive performance with high accuracy and confidence values. While KNN and Random Forest are computationally more demanding, all three models contribute unique perspectives on stroke prediction. The choice of model ultimately depends on research needs such as interpretability, accuracy, and computational resources. Combining multiple models could further improve predictive performance and offer more comprehensive assessments of stroke risk. Our findings align with previous studies that have used ML for stroke prediction, but our integration of RNA-seq data adds a novel molecular-level dimension.

Despite promising results, this study has limitations. The dataset consisted of only 40 samples (20 stroke patients and 20 controls), which may limit generalizability and statistical power. Additionally, model evaluation relied on a single train-test split without repeated randomization or cross-validation, which may introduce sampling bias and overestimate performance. Although our feature selection was focused on biologically relevant genes, incorporating additional omics data or clinical variables could improve predictive accuracy. Future research should validate these findings in larger, independent cohorts using rigorous validation methods such as k-fold cross-validation, and explore integrating molecular signatures into clinical workflows to support real-world diagnostic and therapeutic decision-making.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated the potential of machine learning techniques, including Random Forest Classification, the CHAID Algorithm, and K-Nearest Neighbors, in predicting and classifying ischemic stroke using RNA-seq data. Each model offered unique insights and strengths, highlighting the importance of ML in advancing stroke diagnosis and treatment. While the results are promising, further research and optimization are needed to enhance model performance and demonstrate their practical integration into clinical workflows.

The findings suggest that combining genomic data with advanced computational techniques can enable earlier detection and a deeper understanding of ischemic stroke mechanisms. Future studies should expand the dataset and incorporate additional omics layers to improve model robustness and generalizability. Ultimately, the application of ML in stroke research holds significant promise for improving diagnostic accuracy and personalizing treatment strategies, paving the way for more effective stroke management and better patient outcomes.

Acknowledgement

We sincerely thank Ms. Nahid Nemati and Mr. Hossein Hosseini, Ph.D. candidates in Systems Biomedicine at the Pasteur Institute of Iran, for their invaluable support and contributions.

Funding sources

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical statement

This study did not involve human participants, animals, or biological samples; therefore, ethical approval was not required.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest relevant to this study.

Author contributions

Mina Rahmati: Data preprocessing, machine learning modeling, and drafting the manuscript. Masoud Arabfard: Supervision, statistical analysis, model evaluation, and manuscript revision. Both authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability statement

The raw RNA-seq gene expression data utilized in this study are publicly accessible in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository under the accession number GSE22255. The analyzed datasets and associated computational findings are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author, Masoud Arabfard.

Editorial: Original article |

Subject:

Basic Medical Sciences

Received: 2024/11/13 | Accepted: 2025/05/26 | Published: 2025/06/1

Received: 2024/11/13 | Accepted: 2025/05/26 | Published: 2025/06/1

References

2. Putaala J. Ischemic Stroke in Young Adults. Continuum (Minneapolis, Minn). 2020;26(2):386-414. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

3. Lim H, Park Y, Hong JH, Yoo K-B, Seo K-D. Use of machine learning techniques for identifying ischemic stroke instead of the rule-based methods: a nationwide population-based study. Eur J Med Res. 2024;29(1):6. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

4. Rahmati M, Ferns GA, Mobarra N. The lower expression of circulating miR-210 and elevated serum levels of HIF-1α in ischemic stroke; Possible markers for diagnosis and disease prediction. J Clin Lab Anal. 2021;35(12):e24073. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

5. Li W, Shao C, Zhou H, Du H, Chen H, Wan H, et al. Multi-omics research strategies in ischemic stroke: A multidimensional perspective. Ageing Res Rev. 2022;81:101730. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

6. Patil S, Rossi R, Jabrah D, Doyle K. Detection, diagnosis and treatment of acute ischemic stroke: current and future perspectives. Front Med Technol. 2022:4:748949.

2022;4:748949. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

7. Wardlaw JM, Mair G, Von Kummer R, Williams MC, Li W, Storkey AJ, et al. Accuracy of automated computer-aided diagnosis for stroke imaging: a critical evaluation of current evidence. Stroke. 2022;53(7):2393-403. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

8. Ruksakulpiwat S, Phianhasin L, Benjasirisan C, Schiltz NK. Using Neural Networks Algorithm in Ischemic Stroke Diagnosis: A Systematic Review. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2023;16:2593-602. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

9. Daidone M, Ferrantelli S, Tuttolomondo A. Machine learning applications in stroke medicine: advancements, challenges, and future prospectives. Neural Regen Res. 2024;19(4):769-73. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

10. Wang J, Gong X, Chen H, Zhong W, Chen Y, Zhou Y, et al. Causative Classification of Ischemic Stroke by the Machine Learning Algorithm Random Forests. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022;14:788637. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

11. Jabal MS, Joly O, Kallmes D, Harston G, Rabinstein A, Huynh T, et al. Interpretable Machine Learning Modeling for Ischemic Stroke Outcome Prediction. Front Neurol. 2022;13:884693. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

12. Krug T, Gabriel JP, Taipa R, Fonseca BV, Domingues-Montanari S, Fernandez-Cadenas I, et al. TTC7B emerges as a novel risk factor for ischemic stroke through the convergence of several genome-wide approaches. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32(6):1061-72.

. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

13. Yahiya Adam S, Yousif A, Bashir MB. Classification of Ischemic Stroke using Machine Learning Algorithms. International Journal of Computer Applications. 2016;149(10):26-31. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

14. Hong S, Kim H-W, Walton B, Kaboi M. The Intersectionality of Factors Predicting Co-occurring Disorders: A Decision Tree Model. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2024;22(6):1-24. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

15. Althuwaynee OF, Pradhan B, Park H-J, Lee JH. A novel ensemble decision tree-based CHi-squared Automatic Interaction Detection (CHAID) and multivariate logistic regression models in landslide susceptibility mapping. Landslides .2014;11:1063–78. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

16. Zhang Z. Introduction to machine learning: k-nearest neighbors. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4(11):218. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

17. Halder RK, Uddin MN, Uddin MA, Aryal S, Khraisat A. Enhancing K-nearest neighbor algorithm: a comprehensive review and performance analysis of modifications. J Big Data. 2024;11(1):113. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

18. Arabfard M, Najafi A, Rezaei E. Predicting COVID-19 Models for Death with Three Different Decision Algorithms: Analysis of 600 Hospitalized Patients. Applied Biotechnology Reports. 2023;10(2):1018-24. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

19. Pandian JD, Gall SL, Kate MP, Silva GS, Akinyemi RO, Ovbiagele BI, et al. Prevention of stroke: a global perspective. Lancet. 2018;392(10154):1269-78. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

20. Montaner J, Ramiro L, Simats A, Tiedt S, Makris K, Jickling GC, et al. Multilevel omics for the discovery of biomarkers and therapeutic targets for stroke. Nat Rev Neurol. 2020;16(5):247-64. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

21. Zou R, Zhang D, Lv L, Shi W, Song Z, Yi B, et al. Bioinformatic gene analysis for potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets of atrial fibrillation-related stroke. J Transl Med. 2019;17(1):45. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

22. Daidone M, Ferrantelli S, Tuttolomondo A. Machine learning applications in stroke medicine: advancements, challenges, and future prospectives. Neural Regen Res. 2024;19(4):769-73. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

23. Shah YAR, Qureshi SM, Qureshi HA, Shah S, Shiwlani A, Ahmad A. Artificial Intelligence in Stroke Care: Enhancing Diagnostic Accuracy, Personalizing Treatment, and Addressing Implementation Challenges. IJARSS. 2024;2(10):855-86. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

24. Asif S, Wenhui Y, ur-Rehman S-, ul-ain Q-, Amjad K, Yueyang Y, et al. Advancements and Prospects of Machine Learning in Medical Diagnostics: Unveiling the Future of Diagnostic Precision. Arch Comput Methods Eng. 2024;32(2):853–83. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

25. Fernandes JN, Cardoso VE, Comesaña-Campos A, Pinheira A. Comprehensive Review: Machine and Deep Learning in Brain Stroke Diagnosis. Sensors (Basel). 2024;24(13):4355. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

26. Deshpande D, Chhugani K, Chang Y, Karlsberg A, Loeffler C, Zhang J, et al. RNA-seq data science: From raw data to effective interpretation. Front Genet. 2023;14:997383. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

27. Zhou L, Pan S, Wang J, Vasilakos A. Machine learning on big data: Opportunities and challenges. Neurocomputing. 2017;237:350-61. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

28. Heo J, Yoon JG, Park H, Kim YD, Nam HS, Heo JH. Machine learning-based model for prediction of outcomes in acute stroke. Stroke.

2019;50(5):1263-5. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

29. Diaz-Uriarte R, Gómez de Lope E, Giugno R, Fröhlich H, Nazarov PV, Nepomuceno-Chamorro IA, et al. Ten quick tips for biomarker discovery and validation analyses using machine learning. PLoS Comput Biol. 2022;18(8):e1010357. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

30. Perakakis N, Yazdani A, Karniadakis GE, Mantzoros C. Omics, big data and machine learning as tools to propel understanding of biological mechanisms and to discover novel diagnostics and therapeutics. Metabolism. 2018:87:A1-A9. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

31. Imran B, Wahyudi E, Subki A, Salman S, Yani A. Classification of stroke patients using data mining with adaboost, decision tree and random forest models. ilk. J. Ilm. 2022;14(3):218-28. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

32. Mu Q, Zhang Y, Gu L, Gerner ST, Qiu X, Tao Q, et al. Transcriptomic Profiling Reveals the Antiapoptosis and Antioxidant Stress Effects of Fos in Ischemic Stroke. Front Neurol. 2021;12:728984. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

33. Kurushima H, Ohno M, Miura T, Nakamura TY, Horie H, Kadoya T, et al. Selective induction of DeltaFosB in the brain after transient forebrain ischemia accompanied by an increased expression of galectin-1, and the implication of DeltaFosB and galectin-1 in neuroprotection and neurogenesis. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12(8):1078-96. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

34. Wang SK, Zhang H, Hu CY, Liu JF, Chadha S, Kim JW, et al. FAM83H and Autosomal Dominant Hypocalcified Amelogenesis Imperfecta. J Dent Res.

2021;100(3):293-301. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

35. Aubrey BJ, Strasser A, Kelly GL. Tumor-Suppressor Functions of the TP53 Pathway. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2016;6(5):a026062. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

36. Meng F-d, Ma P, Sui C-g, Tian X, Jiang Y-h. Association between cytochrome P450 1A1 (CYP1A1) gene polymorphisms and the risk of renal cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2015;5(1):8108. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

37. Carnwath TP, Demel SL, Prestigiacomo CJ. Genetics of ischemic stroke functional outcome. J Neurol. 2024;271(5):2345-69. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

38. Peng C, Ding Y, Yi X, Shen Y, Dong Z, Cao L, et al. Polymorphisms in CYP450 Genes and the Therapeutic Effect of Atorvastatin on Ischemic Stroke: A Retrospective Cohort Study in Chinese Population. Clin Ther. 2018;40(3):469-77.e2. [View at Publisher] [DOI:] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

39. Zhang S, Li X, Zong M, Zhu X, Wang R. Efficient kNN classification with different numbers of nearest neighbors. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst.

2018;29(5):1774-85. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

40. Wang X, Zhang XY, Liao N-Q, He Z-H, Chen Q-F. Identification of ribosome biogenesis genes and subgroups in ischaemic stroke. Front Immunol.

2024;15:1449158. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

41. Zhang Y, Li N, Kobayashi S. Paxillin participates in the sphingosylphosphorylcholine-induced abnormal contraction of vascular smooth muscle by regulating Rho-kinase activation. Cell Commun Signal. 2024;22(1):58. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

42. Yi J-H, Park S-W, Kapadia R, Vemuganti R. Role of transcription factors in mediating post-ischemic cerebral inflammation and brain damage. Neurochem Int. 2007;50(7-8):1014-27. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

43. German AE, Mammoto T, Jiang E, Ingber DE, Mammoto A. Paxillin controls endothelial cell migration and tumor angiogenesis by altering neuropilin 2 expression. J Cell Sci. 2014;127(Pt 8):1672-83. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

44. Liang J, Feng J, Lin Z, Wei J, Luo X, Wang QM, et al. Research on prognostic risk assessment model for acute ischemic stroke based on imaging and multidimensional data. Front Neurol. 2023;14:1294723. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |